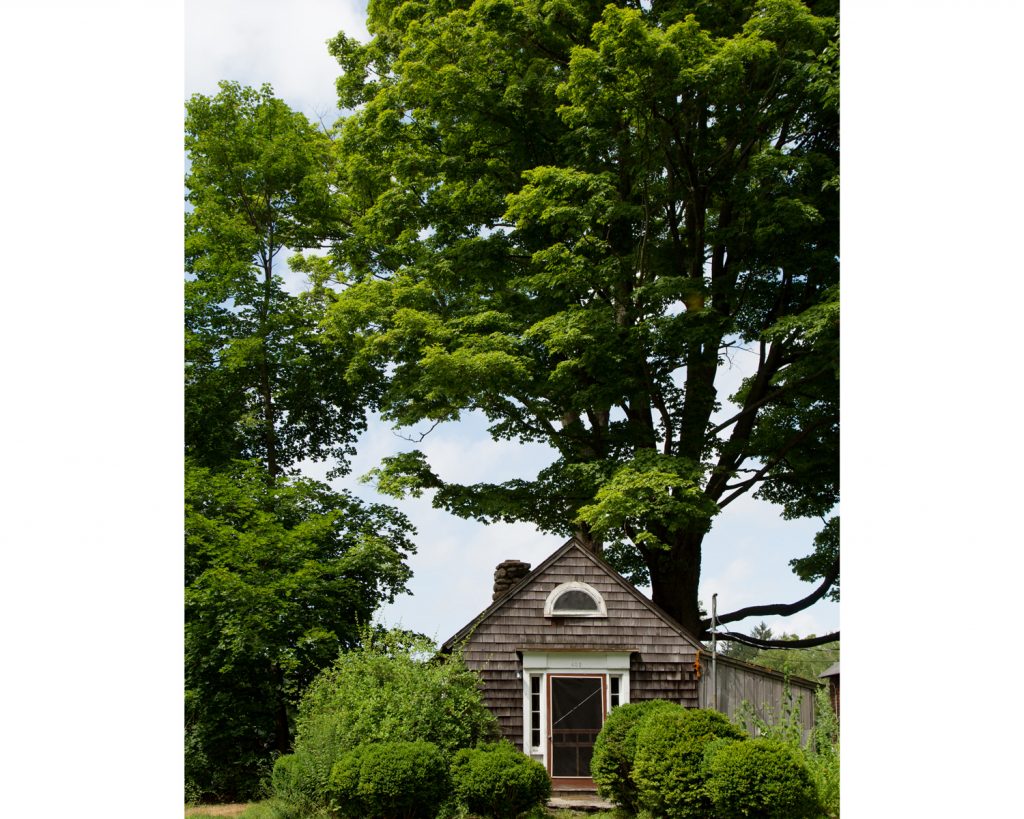

Very few writers’ retreats or artist residencies consider working mothers or single parents when it comes to programming. Enter Emily Simoness, co-founder and executive director of SPACE on Ryder Farm, who identified the issue and got to work. She created a first-of-its-kind family retreat, developed in conjunction with The Lilly Awards, aimed at supporting working parents and their children by providing a space for the artists to create, while also providing a creative and nature-focused program for the artists’ children.

We visited the farm during the week-long Family Residency program and sat down with Emily to learn about the development of the program. We also sat down with two of this year’s participating artists, Georgia Stitt and Deepa Purohit, to learn more about this unique and vital program.

Gina Rattan: How did the family residency come about?

Emily Simoness: In 2014, there was a playwright and a designer who asked if they could bring their kids. Christine Jones, the designer, was curious if she could bring her two boys up with their sitter, and then Sarah Gancher was curious if her son could come up and we made allowances in both instances because it just felt like we should try to make that work.

GR: How did the Lillys get involved?

ES: I somehow got wind that the Lillys were super interested in an initiative like this, so we connected and one of the great benefits of SPACE is that we’re still young and nimble. SPACE is not super bureaucratic or institutionalized. We’re able to pivot in a shorter time than an institution that plans two years in advance. As long as the insurance is good, and we are able to fund the program, we’re able to execute. So I said let’s do it this summer. That was last year, 2015, and we invited six women and their kids and it was good and productive. The kids had programming with Megan Cramer, who’s a really extraordinary educator and if it wasn’t for her I don’t think I would have felt comfortable doing this because I want to make sure the kids have great experiences. The kids had their special time and programming, the parents had time to work on their craft and we all came together for the three meals, and it was a total win. So we opened it up for applications this year.

GR: So it was a test run last summer where you knew the people and could see how it went?

ES: Exactly. I was overwhelmed with the amount of applications, and the level of applications this year. It was articulated in a lot of these applications that I haven’t applied for an opportunity like this in a year or four years or seven years because I didn’t feel invited, or I didn’t feel like I could bring my kid, or I have to choose between my child and my work…all the different reasons that we make the choices that we make.

GR: Were they mostly female applicants?

ES: 99% Female. I felt like I was reading these years of deferred applications, one after the other. It was really hard to pick. We’re contemplating next year doing two weeks just because the need is so strong. It’s also nice in that when there are kids in residence you get up earlier, you have dinner earlier, you go to bed earlier. Everything’s more civilized. It’s not debaucherous. We were leaving dinner yesterday and I was taking a couple of the staff to Trader Joe’s to get food or something and it’s still light outside. It’s nice. And it’s so clear that the demand is high, it’s so obvious that this should be a thing.

GR: Is it more costly for you because you have to put together programming for the kids?

ES: Yeah.

GR: So you have to hire more staff.

ES: There are more people here. Because typically we don’t double-up in rooms – there are double beds in rooms but we don’t double the occupancy in a lot of them, but with the kids we do. So it’s just a bigger number of people, the childcare is really significant.

GR: So who comes to do that?

ES: The child care?

GR: Yeah.

ES: Megan Cramer was at the 52nd Street Project forever. She now works at a school in Atlanta. She’s this amazing educator. Then there are individuals that work with her, Michael Calciano, who was a former SPACE intern, he’s an actor and he works a lot with kids, and then there’s Lindsay Torrey who’s been at the 52nd Street Project who also is an actor and works a lot with kids. They’re the same team that did it last year, so it’s been really nice to have them back.

GR: So it’s an arts camp?

ES: Yeah. Art and farm camp. At 4pm, Alan Ryder, who is my cousin and has the eight sheep on the farm, is going to come and show the kids the sheep. Which is adorable.

GR: They’re gonna love that. They were running after them earlier.

Michelle Tse: You’re a board member of The Lilly Awards, where the idea for this program came about and was developed with Emily and SPACE. I know Julia Jordan was up here last year testing this out. Tell me more.

Georgia Stitt: Julia and Pia [Scala-Zankel] came up last year for the pilot program of this retreat. The idea for this whole thing was born at a Lilly board meeting. We were sitting around talking about the challenges of mid-career women writers and we all identified with the same problems. All of us in our 30s and 40s with kids confessed we had not applied to writers’ retreats for a decade. There comes a point where the thought of leaving your kids for a week or two or three to go work on your art feels, in a way, self-indulgent, and it’s more than your family can handle. So we all stopped applying because it didn’t seem practical to go.

MT: Unless it somehow fits in perfectly with a school break.

GS: Certainly during the school year it’s hard, and then during the summer – I mean, I’ve certainly done it before, where I leave my husband in charge of the kids, but we wind up paying so much in babysitters and hiring other people to fill the second parent role – it’s just this hardship that the whole family absorbs.

MT: And perhaps dads don’t get as much flack for it.

GS: Culturally, it’s less of an issue for dads. I’m not saying there aren’t stay-at-home dads who don’t feel all the same challenges, but culturally, nobody blinks when a dad goes away for a week to work on something. When the mom goes away, the question is always, Where are your kids? Who’s taking care of your kids? My husband doesn’t get asked that.

MT: Right. So this idea was born…

GS: So at this board meeting, we were talking about how many of us had not applied to retreats in a long time. There’s that idea in the corporate world that men make deals on the golf course and women usually aren’t invited to participate. I think it’s changing in some ways and not changing in other ways. But this, the writers’ retreat, is our industry’s golf course, in a way – you meet other writers, you form collaborations, you have this structured but unlimited time to produce your work.

MT: And a welcomed break from the city.

GS: I think all of us in that room said, it’d be different if we could bring our kids with us, but that just seemed so unrealistic. So Marsha [Norman], Julia, and Pia, and the whole team just started running with… well, why is it unrealistic?

MT: Little did you all know, it was very realistic.

GS: Some of the first family-friendly ideas we had were more about taking a pre-existing place like Williamstown or Sundance, partner with a day camp in the area, and perhaps we could provide funding for it. For example, if you go to Williamstown, you could send your kids to the day camp right next door. Out of that idea sprang this idea. Emily stepped up and said, let’s try it!

MT: It’s always such a blessing to have that one person believe in trying.

GS: Julia said [during the pilot program last summer] that everyone had been productive and the kids had a good time, and it was everything it was supposed to be. So we did it again. This is the first year we had open submissions from the writing community at large.

MT: So you applied through that open submission process?

GS: Yes. I’m here as both an artist and as a representative of the Lillys to keep an eye on the retreat to see how it’s going. But in the future, our hope is that no one from the Lillys has to come, that it’s for other artists.

MT: What are you working on this week?

GS: I have two projects that I’m trying to get progress made here. I’m working on The Snow Child for Arena Stage, which is mostly done but I’m doing a lot of editing and shaping work on it. Next week, I’m going to Rhinebeck Writers Retreat with Hunter Foster. He and I are working on a brand new show, so I’m trying to generate some content for that while I’m here.

MT: Has it been a productive week so far?

GS: For me, I’ve been very productive. I came up with a huge to-do list of tasks – compositional and organizational – that I need to get done, and I’m just knocking through them. I hear the kids running around – they’ve been at the lake, they have their grilled cheese sandwiches and their apple slices for snacks…

MT: …and they’re having a dress-up class right now!

GS: Yeah! There are all sorts of projects. The dress-up party is part of Louisa [Thompson]’s project. She’s a set designer and she develops children’s theater. The dressing-up has to do with helping kids identify when clothes become costumes, when they’re not just clothes, and when they’re a part of a character. She brought in a lot of costumes and is helping them build and imagine characters.

MT: We peeked in earlier. The kids are having a ball. It’s like summer camp except mom is an earshot away.

GS: Yeah. Earlier today, we finished lunch, and my youngest was on the hammock and she hurt her finger. She’s six years old, so she came to me crying. I said, come sit with me on the bed and we snuggled for ten minutes, and then she went on her way. Those are the things you miss when you’re not around. Somebody else would’ve comforted her, and she would’ve been fine, but being able to be her mother shouldn’t have to stop just because I’m working.

MT: That’s fantastic.

GS: I’m also less worried about my kids than I would be if I’d left them in the city. Everything for them stops at 6pm here. We have dinner at six, then if the adults still have the energy, they can return to work at nine or so. I guess that break wouldn’t happen if the kids weren’t here…

MT: But that’s the trade off, and your kids are here!

GS: Right.

MT: Wait, hold on – 6pm dinner?

GS: Well, I was here at Ryder Farm once before, and it was a very grown up experience. Meals were all later – that was an adjustment we made yesterday. Dinner on the first night was at seven and all the moms were like, umm…this is going to be hard.

MT: So they made it earlier.

GS: Yeah. All the meals are about half an hour or even an hour earlier than Ryder Farm usually does them. Breakfast here is usually at 9, and we’ve been doing it at 8, 8:30. Dinner is usually at 7 and we’ve been doing it at 6, because the kids are hungry and they don’t want to wait!

MT: And I’m sure the menu is different.

GS: Yes, yesterday we had a beautiful garden salad and stuffed baked potatoes, and the kids were like [mimics their blank stare]. So today they did grilled cheese and potato chips.

MT: Everyone likes grilled cheese and chips. And it’s so nice to be out of the city.

GS: Yeah, I don’t think the kids realize what a treat this is. They’re having a great time, but I don’t think they realize what a big deal this is. They are city kids out of the city, though. They’re scared of the crickets.

MT: Of course.

GS: They were like, “Mom, I can’t sleep! There’s a bug! I can hear it!” I said, “Yes, it’s outside.” There was one bug that was closer so they could hear the buzzing by their window even though it was outside.

MT: But they seem to be loving it here. They’ve got so many activities planned.

GS: Yeah, they’ve planned great things for them. Some of it is creative work, where the kids can create characters, write a play or songs, write a poem – some sort of creative element. This is in addition to things like swimming, and harvesting from the garden what we’re going to eat for dinner.

MT: That’s amazing. I’m jealous.

GS: Today, when they were out at the lake, they collected snails in a pail… I imagine they’ll return them. My kid said they saw flying fish. They’re kind of having guided nature time, which is good.

MT: Getting down and dirty with nature.

GS: Last night they took their baths and they’re just filthy. Filthy with farm, not filthy with New York City.

MT: Clean dirt. Not city dirt.

GS: Yes, it’s just dirt. Not smog and pollution.

[Georgia’s daughter walks in with one of her teachers.]

GS: Come sit.

MT: Honey, did you name your characters?

S. Brown: Yep. One’s Magnificent and one’s Maleficent. They’re sisters. I mean twins.

GS: And one’s good, one’s bad?

SB: Nope.

[Everyone laughs.]

MT: By the way, you’re a really good photographer.

GS: She loves taking pictures.

MT: I left the camera in there for you if you want to take more pictures.

SB: I know. I’m going to go check out the puppy.

Michelle Tse: How did you hear about SPACE?

Deepa Purohit: I applied last year, when a friend of mine told me about it. I’m coming back here for a week on my own in September and she’s coming too. Her name is Monet Hurst-Mendoza. She’s also a writer and we actually were in the theater company I started together. We’re pretty close colleagues and she had mentioned it and so I looked it up and thought, this looks kind of cool.

MT: Was it the working farm program?

DP: I applied to the working farm but when I was applying I was like, Can I really be away for five weeks? It wasn’t a problem because I didn’t get into it, but they offered me a week residency, which I said yes to. I had never been on an actual retreat before, so that was my first writers’ retreat ever, and that was last July.

MT: Did it change your habits of working since it was your first retreat?

DP: It was great because I have never had the time to sit every day and have a routine for writing, so there were actually a few things routine-wise that I actually kept from that time. I mean, clearly I’m not able to write for eight hours a day because I work a couple other jobs to help pay the bills, but key routines have increased the amount of time I’m writing and my efficiency.

MT: That’s awesome. How did you hear about the Family Residency program?

DP: My husband was in this play Dry Powder that Sarah Burgess wrote here and these guys had a fundraiser. They asked him to join Sarah at the fundraiser for SPACE and asked if we would both come. Emily asked if I wanted to apply for the Family Residency and I said I was thinking about it. I applied and got in. I was considering it, initially, before she asked me, but I just wasn’t sure what my son’s schedule was going to be and when his camps were going to run. But that prompt pushed me to apply. The more I thought about it…I haven’t sent my son to sleepaway camp. I’m not that interested in being apart from him, so this is great. It’s a great opportunity.

MT: And the kids have their own schedule and their own classes.

DP: Yeah exactly, and it’s nice because I’m not the kind of mom that needs to be in all day activities. I like spending time with him, I like having our evenings and our meals, but I like him doing his thing.

MT: What are you working on this week?

DP: I’m working on a piece that I worked on last year here. It’s a very personal piece in that…I met a woman ten years ago who turned eighty this year. She’s a good friend of mine, and even a better friend now after going through this process, and she’s a Sri Lankan woman who left Sri Lanka in the 1950s, when she was about eighteen. She moved to London and hopped into the jazz scene. She was a really talented singer and piano player, and she kind of, in some ways, fell into and in some ways found her way into jazz, because her father was very passionate about jazz.

MT: I already want to see this story. What’s her name?

DP: Yolande Bavan. She comes from a very specific community in Sri Lanka called the Burgher community, and they’re a very mixed race group of people – they’re a mix of Tamils and Sinhalese and Dutch and Portuguese, but there’s a very European feel to their culture. When the British were there, the Burghers were actually highly educated, they were sort of that class of people that ran a lot of different sectors. Suddenly the British left and the Sinhalese took over and a lot of them left. They moved and migrated because a lot of them were worried about their status in the country so they moved to Australia and England. Some stayed, but she ended up leaving around that time because her father said, you should go to England; there’s nothing here for you here, really.

MT: Wow.

DP: She went to England in 1954 and she just found her way into the jazz scene. She had been listening to jazz music a lot in Sri Lanka – she would tell these stories about her dad who would get these guys, these Americans, who would come to the docks in Colombo and they’d have all these jazz records. He’d go down to the docks and trade jazz records. He introduced her to Duke Ellington and all the people who were not doing Dixieland because at that time, Dixieland was really big. They were moving into bebop and stuff like Count Basie, that were really going into this complex jazz stuff so she got really into that.

MT: So she found her art and stuck with it.

DP: She started acting in theater and TV and then she was, in her eyes, plucked. She ended up having this range and this ability to hear music and mimic it right away, is the short story of her coming to the States.

MT: Why tell her story?

DP: Her story is really interesting and the reason I’m drawn to it is because, number one, when she was doing readings and things for me, she was in her 70s playing all the mom roles in my plays. She started to tell me about her life and I was like, who’s going to tell her story? She’s been around some really famous people – she was a protege of Billie Holiday’s, she knew Sarah Vaughan and Joe Williams, these big people – and in the jazz circles some people know her name but beyond that not really, and in the Sri Lankan world, definitely, she’s gone back and given concerts and things and I thought, I’m going to tell her story. But it’s not going to be a bio-play, it’s gonna be something cooler.

MT: Of course.

DP: So the last three years I’ve been doing interviews with her, taping them, transcribing them, writing drafts of the play, and really trying to find: what is the play? What is the story? Last summer when I was here, I was in a real block, and a friend who was here, who I met here at the farm, is an Australian playwright – she’s actually based in London now – she said, “You know what, it really sounds like you need to get Yolande, you, and the play in a room and do this exercise and just write, see what they all say to each other.” I thought, I’ll try whatever, I’m so blocked with this. I had so much material and I didn’t know what to do with it. I got them in the room and I wrote crazy amounts of material and created a play that was about creating this play and our relationship.

MT: How has the piece progressed?

DP: I did a reading of it in the fall of last year, and she was in it, because the whole thing was that I want her to be in what I’m writing. It was a very bizarre, meta-experience because a lot of it is about our tussles and differences around it and what we wanted this thing to be. A lot of the writing came from conversations out of which tension came, and both of us are non-confrontational, so there were very interesting dynamics. She did the reading full-heartedly and was amazing in it. It was a first-draft play and had a lot of flaws and I was ready to rewrite, and in the meantime, one of my friends said, “You need to take a break from the play and then go back to it.” And I thought, no, I can’t, she’s turning eighty. I need her to be in this play.

MT: I get that though, sometimes you need a mental break.

DP: I did take a break. I wrote another piece and came back to this, this summer. And as I came back to it, I realized, oh my god I’m in another block. I was having a lot of conversations with her and she was asking, what’s this play going to be? And I was not giving her the answer because I didn’t know. She had very much been saying she wanted to do a play with songs about her life, people tell me I should write a book. And I’m not going to be that person. Even though I have all the material, I don’t want to write that book. So there was a lot of that dynamic going on, and I thought, I can’t do this. I’m just going to write what she wants.

So I’m writing a cabaret of songs and her telling her story, directly addressing the audience, which is something I never wanted to do – totally traditional, whatever. I started doing that this summer through a class I was taking, and every time I walked into the class I would be like [sighs]. I was stuck again. So I thought, let’s trying having this conversation again. I brought a scene into class that was me and her having conversation, and everybody was like, whoa, that is really interesting. So now I’m back in that place, but I think I’m taking everything that I learned with me over the last three years.

MT: So the piece is taking on a new form.

DP: I kind of don’t trust myself at this point, because I’ve felt like this four times, but I think this is part of the process to write a play about a person you’re close to, who’s alive, who you’re interacting with all the time – we’re kind of codependent. She’s a bull and she’s been through a ton in her life and that is the honor that I want to bestow on the stage, not only the flaws between us.

MT: How has your personal relationship informed and shifted the piece?

DP: There are two things that happened. She took a fall about four years ago, onstage. It was a plebeian kind of fall where she missed her mark onstage and she fell backwards and missed a chair. So she went on with the show and the rest of the run but what happened in that fall was that she had crushed her entire coccyx and so she was in excruciating pain and then had to have a nine-hour surgery to reassemble her back. So for the last four years she’s been in recovery for that and she’s a woman that’s a mover and a shaker. She’s tiny, she’s always on the move – her life has always been on the move. She’s crossed oceans, and I think I realized for the first time this last summer was, oh that’s what these few years have been about, being still.

Around the time she took that fall, my father passed away. He had been sick for a couple of years. I think we met at a time where we were both facing mortality in a different way. The other piece is that I’m officially realizing I’m in middle-age. That’s also about looking on the horizon thinking I’m not thirty-something and I have forever to do something, and what does that mean for me as an artist when I’ve spent the last fifteen years struggling to even define myself as an artist? I was an actor and I still do act. I wonder if I’ll act again. I write – I’m really just emerging as a writer in middle age – not really having done a lot of writing that prior to it…so there are a lot of issues around mortality for both of us that are really different. So I do imagine this piece like we’re looking in the mirror, but the mirror is open and we’re looking really at each other.

MT: And it must be interesting to explore mortality in a place that is as old as this. The farm and its structures are older than the town, but everywhere you look, new life is growing around you.

DP: Yeah, this house is interesting. There’s all these artifacts from all these different times. I don’t necessarily want to walk through this house because I don’t relate to it culturally, because there are all these pictures, of white people, and there’s this feeling of it being an American place, and I don’t have a legacy in that way in the United States.

MT: As an immigrant, I get that.

DP: If I were to walk into a stone house that was only cooled by the fact that it’s stone, and it’s concrete and people are lying their mats on the floor or they have beds or whatever, that seems more a part of my past and time. Where Yolande is interesting because she’s got so much European culture in her blood, this house would actually be quite evocative for her, even though she’s coming from a South Asian country. A lot of her life has been as an outsider, even within her own country in so many different ways. As a woman…what woman in the 1950s was leaving her country, not getting married, and going to sing jazz?

MT: Unheard of, especially in Asia.

DP: All these women who were in school with her were getting married, cooking curries and having kids, and that wasn’t her. So there’s a real trailblazer aspect to her and her story and I stand on her shoulders. So many of us do. And there are lots of people like her but this story is unheard.

In the Asian community, there are so many people whose shoulders we stand on but we don’t even know unless we really ask. And I would say, for me, I’ve taken it for granted, but every time I look at the material or go back to listen to her interviews…she’s like a regular person to me and we have a regular relationship that’s fraught with love and annoyances or whatever but then I’ll listen to these things and I’ll just be like…holy shit. This woman is on her own, just trailblazing, even now at the age of 80.

Shea Renne is an actress based in New York City. She is currently in Here Lies Love at the Seattle Repertory Theatre. Other credits include: Broadway: Allegiance (Betsy Tanaka). Regional: Spring Awakening (Ilse, The Hangar Theatre), Seussical The Musical (Bird Girl, The St. Louis Muny), West Side Story (Rosalia, Music Theatre Wichita), South Pacific (Liat, MTW) Footloose (Urleen, Fulton Theatre). She is a proud member of the Actors’ Equity Association and graduate of the University of Michigan.

Shea Renne is an actress based in New York City. She is currently in Here Lies Love at the Seattle Repertory Theatre. Other credits include: Broadway: Allegiance (Betsy Tanaka). Regional: Spring Awakening (Ilse, The Hangar Theatre), Seussical The Musical (Bird Girl, The St. Louis Muny), West Side Story (Rosalia, Music Theatre Wichita), South Pacific (Liat, MTW) Footloose (Urleen, Fulton Theatre). She is a proud member of the Actors’ Equity Association and graduate of the University of Michigan.

CHRISTINE TOY JOHNSON is an award-winning writer, actor, filmmaker, director and advocate for inclusion. Her plays and musicals have been developed and produced at such places as the Roundabout Theatre Company, The O’Neill Theater Center, The Meryl Streep/IRIS Writers Lab, Crossroads Theatre, The Barrow Group, Prospect Theater Company, CAP21, The Weston Playhouse, Gorilla Rep, Leviathan Lab and Village Theatre. A collection of her written work is included in the Library of Congress Asian Pacific American Performing Arts Collection.

CHRISTINE TOY JOHNSON is an award-winning writer, actor, filmmaker, director and advocate for inclusion. Her plays and musicals have been developed and produced at such places as the Roundabout Theatre Company, The O’Neill Theater Center, The Meryl Streep/IRIS Writers Lab, Crossroads Theatre, The Barrow Group, Prospect Theater Company, CAP21, The Weston Playhouse, Gorilla Rep, Leviathan Lab and Village Theatre. A collection of her written work is included in the Library of Congress Asian Pacific American Performing Arts Collection.

I am an Iranian/American actress, born and raised in Tehran, Iran. I moved to New York in my teens, where I discovered my love of acting and story telling. I am a graduate from the esteemed Maggie Flanigan Studio. I continue building my resume of a variety of characters from weak to strong, while exploring their humanity and fragility. I am fluent in Persian/Farsi and a transgender advocate, as well as a voice for immigrant issues and women’s issues. I am also involved in writing and co-writing original LGBT stories to shed light on an otherwise under represented community.

I am an Iranian/American actress, born and raised in Tehran, Iran. I moved to New York in my teens, where I discovered my love of acting and story telling. I am a graduate from the esteemed Maggie Flanigan Studio. I continue building my resume of a variety of characters from weak to strong, while exploring their humanity and fragility. I am fluent in Persian/Farsi and a transgender advocate, as well as a voice for immigrant issues and women’s issues. I am also involved in writing and co-writing original LGBT stories to shed light on an otherwise under represented community.

Timothy Huang is a New York based writer of new musical theater. His full length musical Costs of Living was the recipient of the 2015 New American Musical Award, and the 2015 Richard Rodgers Award. Other works include Peter and the Wall (2013 Rhinebeck Retreat), And the Earth Moved, (CAP21) Death and Lucky (MacDowell Fellowship), the song cycle LINES (NYMF), A Relative Relationship (Winner, Best Musical, 2013 SoundBites Festival) and Missing Karma (2016 Samuel French OOB Short Play Festival). He is the creator of the one person musical The View From Here (cast album available wherever digital music is sold) and was a 2012 Dramatists Guild Fellow. He is also the recipient of the 2013 Jerry Harrington Award, a Fred Ebb Award Finalist and a two time Jonathan Larson Grant finalist. His song Everything I Do, You Do (with co-lyricist Sara Wordsworth) was recorded by Sutton Foster for the charity album Over the Moon: The Broadway Lullaby Project. To see a website made before the advent of smart phones, please visit

Timothy Huang is a New York based writer of new musical theater. His full length musical Costs of Living was the recipient of the 2015 New American Musical Award, and the 2015 Richard Rodgers Award. Other works include Peter and the Wall (2013 Rhinebeck Retreat), And the Earth Moved, (CAP21) Death and Lucky (MacDowell Fellowship), the song cycle LINES (NYMF), A Relative Relationship (Winner, Best Musical, 2013 SoundBites Festival) and Missing Karma (2016 Samuel French OOB Short Play Festival). He is the creator of the one person musical The View From Here (cast album available wherever digital music is sold) and was a 2012 Dramatists Guild Fellow. He is also the recipient of the 2013 Jerry Harrington Award, a Fred Ebb Award Finalist and a two time Jonathan Larson Grant finalist. His song Everything I Do, You Do (with co-lyricist Sara Wordsworth) was recorded by Sutton Foster for the charity album Over the Moon: The Broadway Lullaby Project. To see a website made before the advent of smart phones, please visit

ANN HARADA is best known for playing Christmas Eve in the Broadway and West End productions of AVENUE Q and stepsister Charlotte in RODGERS + HAMMERSTEIN’S CINDERELLA. Other Bway: Madame Thenardier in LES MISERABLES (revival), 9 TO 5, SEUSSICAL, and M. BUTTERFLY. She performed her solo concert in Lincoln Center’s American Songbook series in 2014. Film: SISTERS, TROUBLE, YOUTH IN OREGON, ADMISSION, HOPE SPRINGS, FEEL, HAPPINESS. TV includes: SMASH (recurring as Linda, the Stage Manager), LIPSTICK JUNGLE, 30 ROCK, DOUBT, THE GOOD WIFE, HOUSE OF CARDS, MASTER OF NONE, THE JIM GAFFIGAN SHOW (recurring as Stevie, Jim’s clueless agent).

ANN HARADA is best known for playing Christmas Eve in the Broadway and West End productions of AVENUE Q and stepsister Charlotte in RODGERS + HAMMERSTEIN’S CINDERELLA. Other Bway: Madame Thenardier in LES MISERABLES (revival), 9 TO 5, SEUSSICAL, and M. BUTTERFLY. She performed her solo concert in Lincoln Center’s American Songbook series in 2014. Film: SISTERS, TROUBLE, YOUTH IN OREGON, ADMISSION, HOPE SPRINGS, FEEL, HAPPINESS. TV includes: SMASH (recurring as Linda, the Stage Manager), LIPSTICK JUNGLE, 30 ROCK, DOUBT, THE GOOD WIFE, HOUSE OF CARDS, MASTER OF NONE, THE JIM GAFFIGAN SHOW (recurring as Stevie, Jim’s clueless agent).

Marsha Norman won a Pulitzer for her play ‘night, Mother, a Tony for The Secret Garden on Broadway and a Tony nomination for her book for The Color Purple.

Marsha Norman won a Pulitzer for her play ‘night, Mother, a Tony for The Secret Garden on Broadway and a Tony nomination for her book for The Color Purple.

Rachel Griffin is a 2015-2016 Dramatists Guild Fellow whose compositions have been showcased at 54 Below, 47th St Theatre, the Musical Theatre Factory, Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, the New Light Theatre Project, Rockwood Music Hall, The Living Room, and Hotel Cafe. She has won two National songwriting contests, the NPR Historic Songwriting Contest and the American Idol Underground Songwriting Contest. Griffin’s work has been featured in The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, The Mighty, PBS News Hour chats, Art With Impact and on CBS News. She has created several viral videos, blogs, and the viral Twitter campaign #imnotashamed. She is writing full length musical about mental health that can be found at

Rachel Griffin is a 2015-2016 Dramatists Guild Fellow whose compositions have been showcased at 54 Below, 47th St Theatre, the Musical Theatre Factory, Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, the New Light Theatre Project, Rockwood Music Hall, The Living Room, and Hotel Cafe. She has won two National songwriting contests, the NPR Historic Songwriting Contest and the American Idol Underground Songwriting Contest. Griffin’s work has been featured in The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, The Mighty, PBS News Hour chats, Art With Impact and on CBS News. She has created several viral videos, blogs, and the viral Twitter campaign #imnotashamed. She is writing full length musical about mental health that can be found at

Lissa Levin is the recipient of the prestigious Kleban Award for her libretto for Twist Of Fate; composer, Ron Abel. The musical comedy won L.A. Weekly’s Musical of the Year and two L.A. Drama Critics Circle Awards, and a Los Angeles Ovation Award nomination for Best Musical. Her play, Sex And Education, first presented at the Kennedy Center’s Page-to-Stage Festival, (New York premiere, Penguin Rep), opens in spring of 2016 at the Laguna Playhouse. She also penned book and lyrics for Jewsical, The Low Bar Mitzvah; Hot Blooded, A Vampire in Rio; and the play, What Would Jesus Do? A twenty-five year veteran of television as a writer producer, Levin’s credits include the Emmy Award winning Mad About You and Cheers; Wkrp In Cincinnati, Family Ties, Brothers, Complete Savages (with Keith Carradine), Thunder Alley (with Ed Asner) and Gloria (with Sally Struthers), amongst many others. Her essay, Pisser, a rant about insufficient stalls in women’s restrooms in theaters, was published by Random House in an anthology of noted female humorists: Life’s A Stitch; later transformed into a theatrical revue co-produced by Levin, a staunch activist, benefiting breast cancer research.

Lissa Levin is the recipient of the prestigious Kleban Award for her libretto for Twist Of Fate; composer, Ron Abel. The musical comedy won L.A. Weekly’s Musical of the Year and two L.A. Drama Critics Circle Awards, and a Los Angeles Ovation Award nomination for Best Musical. Her play, Sex And Education, first presented at the Kennedy Center’s Page-to-Stage Festival, (New York premiere, Penguin Rep), opens in spring of 2016 at the Laguna Playhouse. She also penned book and lyrics for Jewsical, The Low Bar Mitzvah; Hot Blooded, A Vampire in Rio; and the play, What Would Jesus Do? A twenty-five year veteran of television as a writer producer, Levin’s credits include the Emmy Award winning Mad About You and Cheers; Wkrp In Cincinnati, Family Ties, Brothers, Complete Savages (with Keith Carradine), Thunder Alley (with Ed Asner) and Gloria (with Sally Struthers), amongst many others. Her essay, Pisser, a rant about insufficient stalls in women’s restrooms in theaters, was published by Random House in an anthology of noted female humorists: Life’s A Stitch; later transformed into a theatrical revue co-produced by Levin, a staunch activist, benefiting breast cancer research.

Georgia Stitt (composer/lyricist) is currently writing the musicals Snow Child for Arena Stage (Washington, DC) and Big Red Sun for 11th Hour Theatre (Philadelphia). Other shows include Tempest Rock with Hunter Foster, The Danger Year, Mosaic and the commissioned children’s musical Samantha Space, Ace Detective, co-written with Lisa Diana Shapiro for TADA Youth Theater in NYC. Georgia has released three albums of her music: This Ordinary Thursday, Alphabet City Cycle and My Lifelong Love. She music directs concerts and recordings for singers like Laura Benanti, Kate Baldwin, Elena Shaddow, Susan Egan and Robert Creighton, and she writes quite a bit of choral music, including an upcoming oratorio for Tituss Burgess.

Georgia Stitt (composer/lyricist) is currently writing the musicals Snow Child for Arena Stage (Washington, DC) and Big Red Sun for 11th Hour Theatre (Philadelphia). Other shows include Tempest Rock with Hunter Foster, The Danger Year, Mosaic and the commissioned children’s musical Samantha Space, Ace Detective, co-written with Lisa Diana Shapiro for TADA Youth Theater in NYC. Georgia has released three albums of her music: This Ordinary Thursday, Alphabet City Cycle and My Lifelong Love. She music directs concerts and recordings for singers like Laura Benanti, Kate Baldwin, Elena Shaddow, Susan Egan and Robert Creighton, and she writes quite a bit of choral music, including an upcoming oratorio for Tituss Burgess.

Bear Bellinger is an actor, writer, singer, bartender, activist, and all-around trouble maker based in Chicago.

Bear Bellinger is an actor, writer, singer, bartender, activist, and all-around trouble maker based in Chicago.