William Jackson Harper’s impressive debut play Travisville, though set in the 1960s, feels like a contemporary piece tackling issues of race, gentrification, and political revolution. We sat down with cast members Denny Dale Bess, Sheldon Best, Brian D. Coats, Bjorn DuPaty, Lynnette R. Freeman, and Ivan Moore over lunch to discuss the play’s impact and importance in our current political climate.

Margarita Javier: What can you tell us about the character or characters you play?

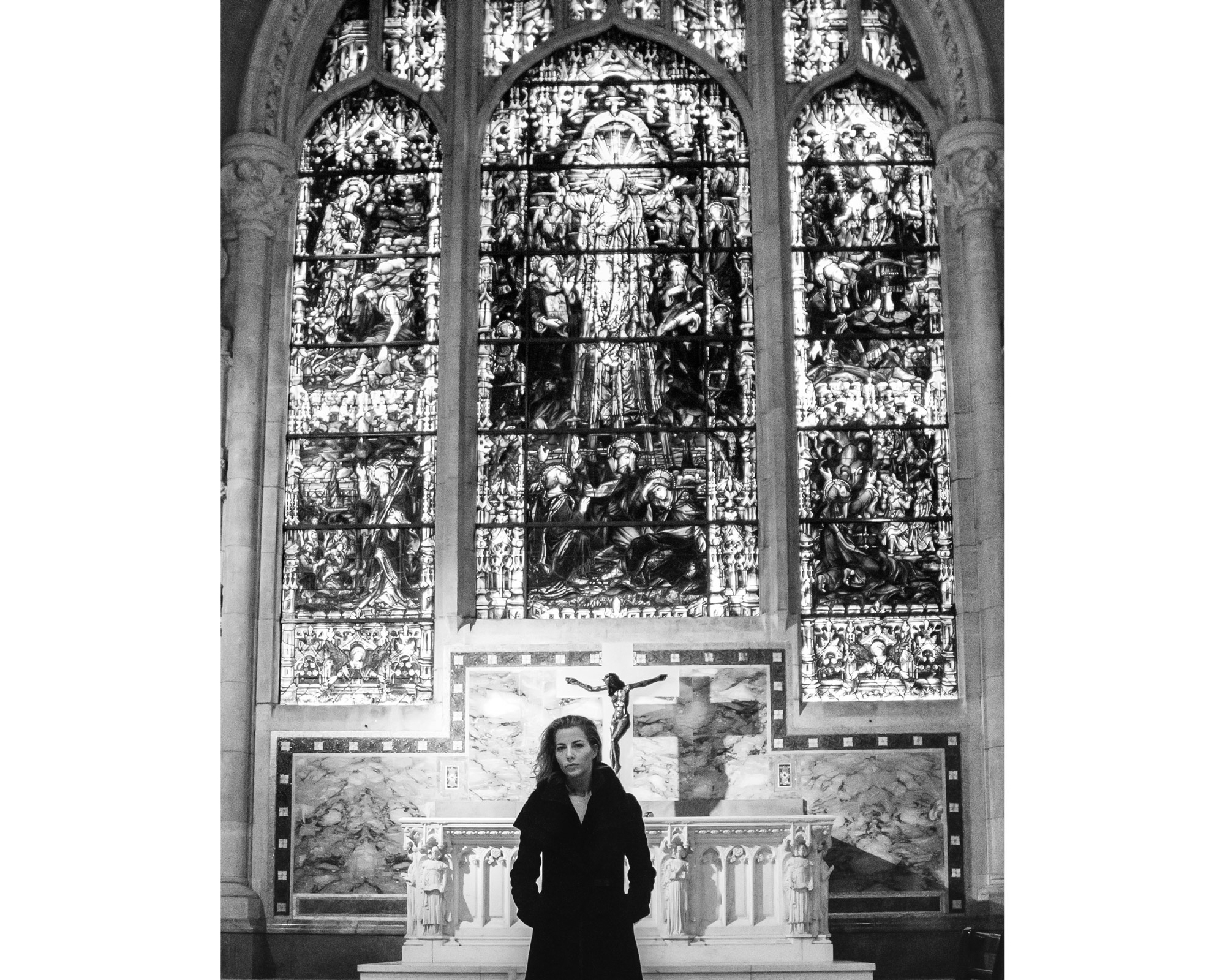

Brian D. Coats: I play Elder Hearst. He’s running things at the Church and the Minister’s Alliance. I think he takes things going on with black people and Civil Rights very personally. He has a protégé and is trying to get him to take his rightful place in the fight in the struggle against all the things that we’re experiencing.

Lynnette R. Freeman: I play Georgia Dawson who is a mother of three. She is a housekeeper and married to Orthel Dawson who is a mechanic in the district that is slated to be displaced for this Travisville project. She is an extremely forthright woman. First and foremost comes her family, so she does everything she can to make her family comfortable and living a good life.

Bjorn DuPaty: I play Ora Fletcher. I would say he’s stuck between the old way and the new way. Obviously things are changing in the world around this time period. I think he recognizes that, but also initially he never really wanted to get into the political side. He was more of a church man. He’s felt like he’s a man of justice doing what’s just, what’s right. And I think that mindset gets him involved in local politics. I think his whole thing was just to be a pastor of a church and to take care of the people of the church and the community. But as we all know, the church was very involved with politics during that time. I think he’s stuck between how things used to be and surviving that way and the new way, being more outspoken and standing for our rights and being more active and proactive. And by the end of the play, I think he makes a choice about which side to land on.

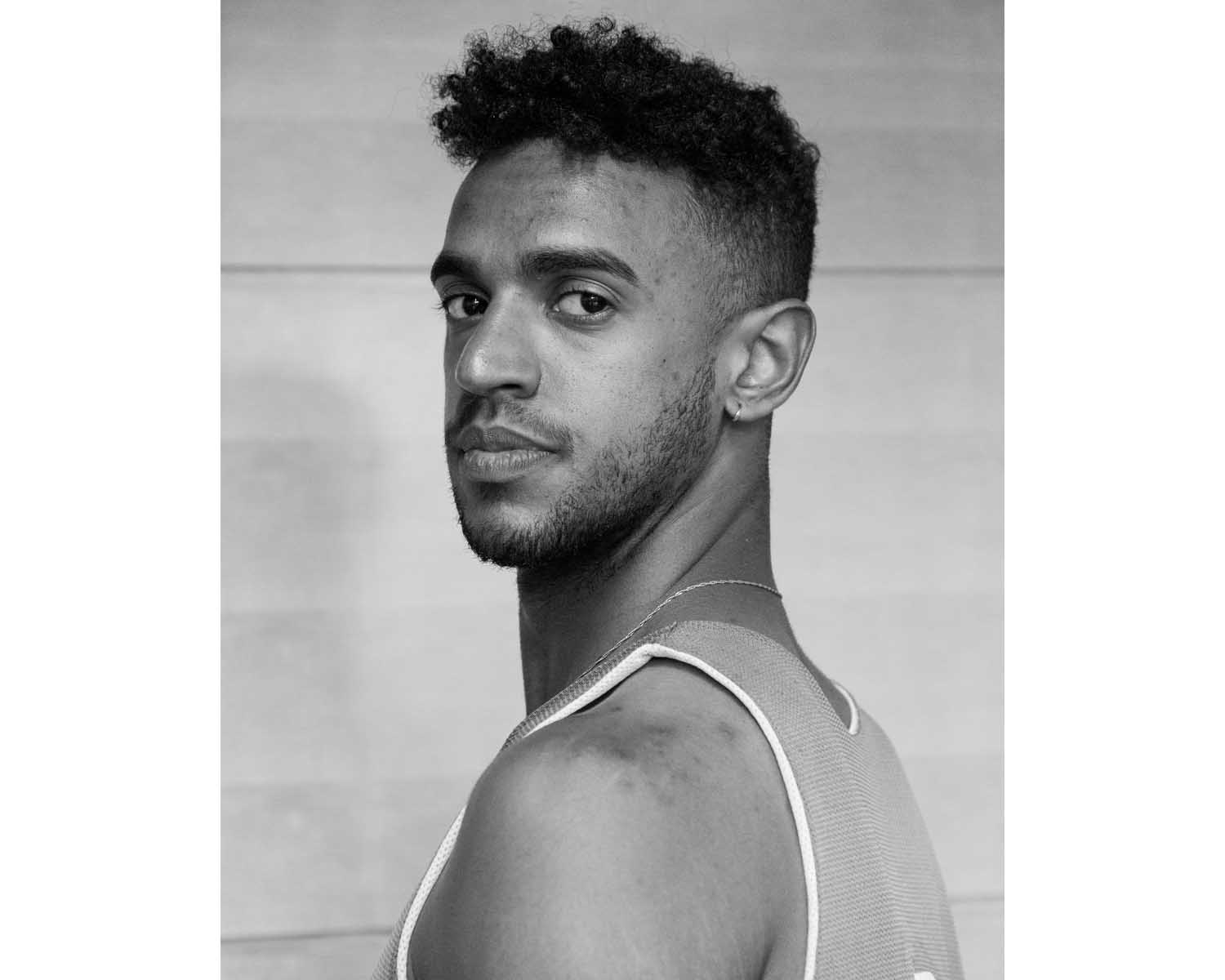

Sheldon Best: I play Zeke Phillips who is a young activist who comes from Atlanta and has come to this town in Texas. He’s working with CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, and has come to this town in order to help uplift people and to get them to move from being complacent with injustice to taking some action, because Zeke has zero tolerance for injustice and is willing to sacrifice in order to move things forward for his people.

Denny Dale Bess: I play two characters. The first one I play is Mayor Gillette. He’s a bit rough and gruff. He’s very blunt, but he is very caring for his community and wants equal rights for black and white citizens. The second character I play is a real estate developer named Honeycutt who is proposing the Travisville Project to the Fannin Gardens district. Honeycutt is more of a cosmopolitan individual and he is intensely a businessman.

Ivan Moore: I play a dual role. I play Minister Howard Mims, commonly known as Jumpy now [laughs]. And one of the townspeople, Howard Birch. Mr. Mims is part of the Alliance. I lean towards more radical side, but I’m not too radical. Howard Birch is one of the older folk that’s lived in a town for many, many years. I know how it works in terms of white black relation. I’m willing to sell my house and get up outta there if I have to. I don’t necessarily appreciate the intervention of the young men coming into town and stirring things up. I would prefer if he just went back to the land of the giants, as it were.

Margarita: The play is Travisville by William Jackson Harper. There’s a lot of buzz about it, a lot of great word of mouth. If you had to describe in a few words what this play is about, what would you say?

Ivan: Gentrification of the ‘60s with racial overtones.

Denny: Individuals trying to get what they need and what they want.

Sheldon: How we demand or seek progress in a society. Do we do it in small steps, small stages? Do we demand what we deserve and get it, and then take the consequences of those demands and use that as a vehicle to move forward? Or do we try to move more gradually?

Bjorn: All progress demands some type of sacrifice.

Margarita: The play is set in the 1960s during the civil rights movement; it’s a new play. Obviously it goes without saying, but it’s something that’s still relevant to today’s society. Like you mentioned —gentrification, racism, the fight for equality. How do you think this play speaks specifically to New York City audiences?

Sheldon: In many respects I think it speaks to who we are in life today, not just in New York but in the world. You guys can correct me if I’m wrong, but the play takes place in a place where nothing was really happening, right? Black people and white people in this town more or less got along. There weren’t lynching, bombings, anything like that. People were comfortable. So take our world now, more or less people are comfortable. There are some extreme things, but for the most part, everybody’s eating, they have a household and they can progress. There’s opportunity. So are you going to stay comfortable or are you going to make sure that equality is really upheld, that the tenants of this country are really upheld? Or are you just going to go along with the flow because that’s what you’ve been doing the majority of your life?

Ivan: I think it addresses a lot of the issues that we have today. You know, we kind of feel that white folks are going to get what they want one way or the other. I think if you ask people of color, minorities in this day and age, the sentiment still runs deep that way. Gentrification is real. It’s happening as we speak. One character says “It’s not personal, it’s business,” and I think that’s justification for a lot of what you do when people are displaced. Some people, like my character, fought the fight for a long time and then you’ve got a young guy who comes along and says how it needs to be done, and that internal tug of war as they had back then, it’s still the same thing. Except we’re not hanging from trees and getting things cut off. Yet. In our current political climate, I think we’re all kind of waiting for stuff like that to happen on some level or another, but right now we just live with the tension that there’s a reality there we can talk about but are not tactile seeing it.

Lynnette: Here in New York specifically, you can’t just talk about gentrification and talk about economic disparity without also talking about race. Look at Brooklyn, at the Atlantic yards, the fact that people didn’t have a choice. You are going to be displaced, period. Whenever I hear Honeycutt and Zeke’s back and forth during the show when talking about Travisville, they’re talking about place that’s prone to flooding. I think it’s very interesting, particularly post Sandy when we found out how vulnerable New York actually is. All of a sudden there were all of these changes, and then people are being moved in order to live in this city farther and farther away from the center of the city, towards the ocean, which is the most susceptible place to flooding. And so you do have to look at that and see those disparities where one person may say it’s just business, but then it’s like, no, people’s lives are now on the line if another really big hurricane comes. I feel like this play puts all of those things together, especially now with Black Lives Matter and whatnot. Maybe people were being told that black and brown folk are not being targeted or racially profiled, but clearly it is happening, and often. And when people protest peacefully, when that is not heard, or when that is painted with a brush stroke that says that people are aggressive or violent, how do we make our voices heard? How do we move towards civil rights being really not only considered but actually followed through? Look at the children being detained, even in New York. I think this play is a really wonderful way to look at the past because many times people will look at the past and say “that’s then.” But a lot of it is still happening now.

Sheldon: One of the things that I found really relevant to New York about this play is the way that people’s latent, just under-the-surface racism comes out when housing issues are on the table. For example, there was a school in Park Slope where they were like, Oh, we’re gonna have these two schools join. And one school had mostly people of color, and the other was mostly white. And the parents at this white school went ballistic.

Margarita: Yeah, and that was supposedly liberal people being overtly racist.

Sheldon: Yeah! And that’s exactly what I think is true of this play and what’s true of New York City, and what’s true today: it’s often people who would consider themselves liberal and say like, we get along and love each other. That’s great. But my character has a line in the play that says, “You don’t have to hate someone to think you’re superior to them.” And once you have that superiority complex, that white supremacy that is right below the surface, once the issue has come forward, that means you’re going to have to confront this in some way. Either when your kids are going to school together or you are going to have to live together, or work together with people you think you deserve better than or you are better than. Those kinds of things can suddenly come out, and they come up with vitriol. It’s true in the play and it’s true in the city today in 2018.

Denny: Acceptance and understanding is something that always comes to mind for me because when Zeke comes to the Fannin Gardens district to disrupt this Travisville project to get people to stand up in his community, the mayor is adamant about going to the minister’s Alliance and getting Elder Hearst to keep his people in line. Because this is a big money moment for this town. We could potentially have a lot of money to get people working together. “White and Negro side by side” is what I say verbatim and that’s when they start to show some change within that old guard to the new guard. Minister Gunn has gotten Zeke to come in from Atlanta to disrupt this and then they slowly start to persuade Minister Fletcher to join their side, but he makes up his own mind later in the play because he wants to honor Elder Hearst’s vision of play ball with the mayor, play ball with city hall. This could work in all of our favor because it will bring revenue to everyone, but at the same time there’s this need to have their own voice. It’s time for things to stop, time for things to change. But I think the mayor is very adamant about swaying that idea until we can get this project past. So he is for both white and black, but at the same time, like Sheldon was saying, when it comes to money and housing, it’s thinking of ourselves first.

Margarita: Right, and the same thing is happening now. This is a broad question, but what can be done? What is the solution? Is it political activism? Peaceful protesting? Revolution?

Denny: I think this play is a start of the conversation.

Ivan: Sit down and have a conversation. Teach people how to treat you. If you sit down and just let people displace you, and you say nothing, they’ll keep doing it. There’s no reason not to, because they know you’re not gonna meet any resistance. I think the thing about this particular play is that you kind of see both sides of the resistance coming in. People who want to resist them and people don’t want to resist, and invariably there’s a price that one of our characters pays for resisting. We’re kind of used to and not used to all at the same time. It’s always different when you read something in the newspaper and then it becomes a little more different when it’s something that becomes very personal to you, you know? We’re living at a time where the issues are really not all that removed from the 1960s or what have you. The activism, the resistance, if you will, it’s still very much alive and well after all these years. They’re still fighting the same battles but just not fighting them all in the same place. So things have not changed all that much.

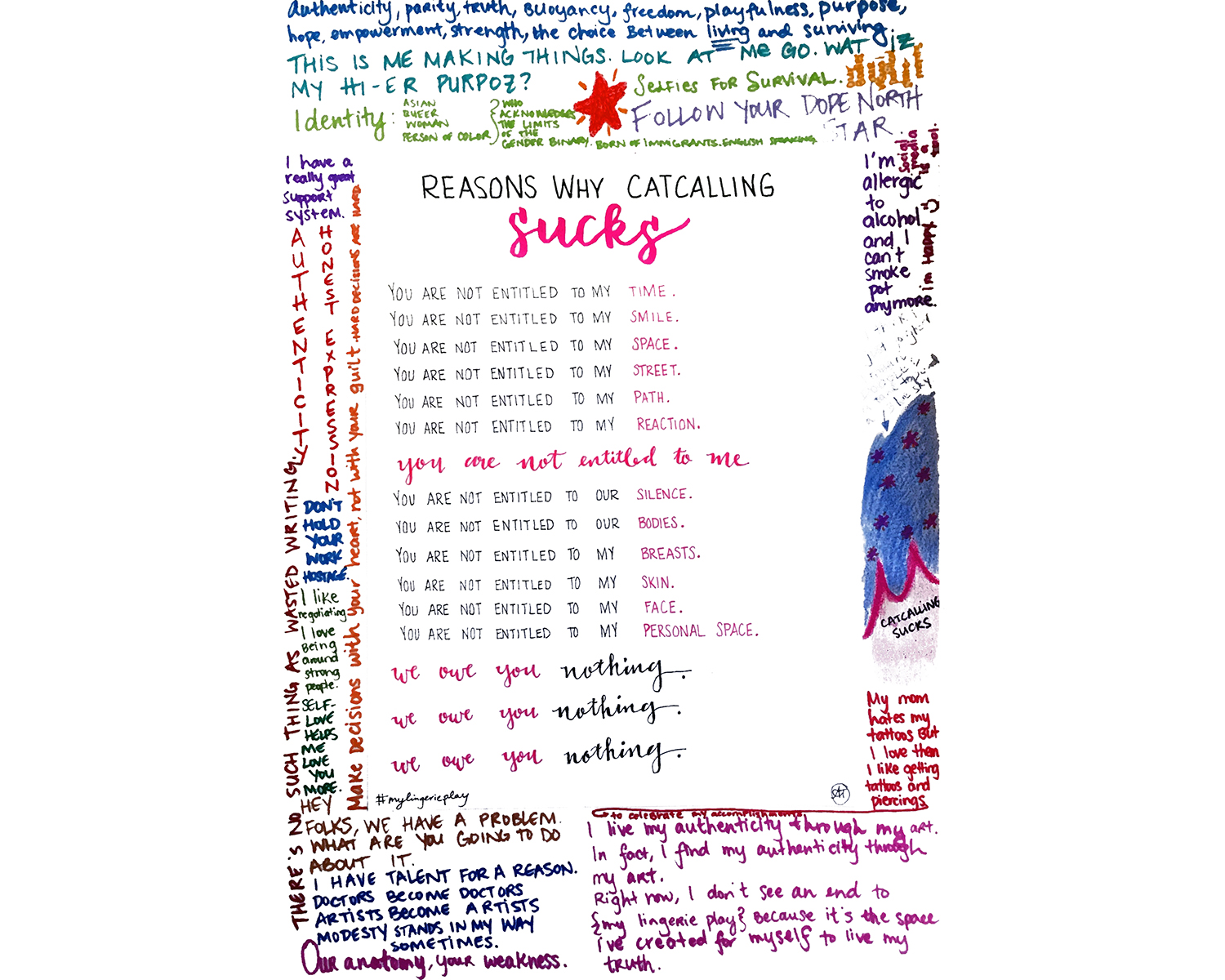

Lynnette: What I think is really funny is in general, this country was very much built with certain inherent biases already entrenched in its creation and its fabric. But then one of the big things that this country was built on was the fact that we can overthrow things and there can be messy revolution and that as Americans we should do that in order to have ourselves better representative forward democracy. Now, that has never actually been true. We say it’s true. But it’s not. And so I think that before we can even address things in full revolution or even peaceful protests, there is a necessity for everyone to speak very frankly about inherent biases, to speak very frankly about racism and sexism and misogyny and all of that. That is literally built into our institutions because it’s hard to move forward when the laws themselves are not fair or built with those same ideals in mind.

Ivan: I’ve always felt that. The one thing I’ve always said is that we always say the laws are not fair. But the laws are fair – for the people they’re written for. Which are not minorities, which are not women. When you want this country to do something that is fair, you have to force it, you have to have them make a law and have them enforce it, anything from not selling slaves to women voting. Up until you made a law, these were things that were all right to do.

Lynnette: And there were laws about that! If you look at people actually following the law, having a slave was part of the law.

Ivan: So when people say the laws are not fair in this country, the laws of very fair in this country to the people they were written for, and that’s not us [laughs].

Bjorn: I’ve gotten to the point where I don’t really see this country getting better unless there is a revolution, and that’s going to take sacrifice and maybe even bloodshed. We can say everything about laws and things like that, but there is still a power structure that is still in place. That’s why we have a guy like Kavanaugh getting in like it doesn’t matter. It does not matter. They can do the investigation for the public eye and say they did that, and it’s funny, as it’s happening, some people go, Well, it’s gonna work this time, and then some people go, That motherfuckers getting in [laughs]. Excuse the language, but you see it. And I feel like a lot of people are starting to see more of it. A few days after Trump got elected, a friend of mine who’s Jewish interviewed me for this thing he was putting together and the first question he asked was, Were you surprised? And I said, Do you want my PC answer or do you want my real answer? He’s all, I want you to be really honest. I was like, Okay, I’ll be honest with you, black people and most people like me, were not surprised at all. And it wasn’t even about trying to be different. It’s just that we’ve seen this story play out in some way or fashion. I always tell people the biggest time that I was ever surprised were two moments: when O.J Simpson got off and when Barack Obama got elected. If you look at both of them, the celebrations were exactly the same. If you really look at it. When O.J got off, people ran in the street talking about We won! We didn’t win shit. But what we did see, finally, was a man of color when all the evidence at the counter said he should be under the jail, he actually got off. That was something we’d never seen before. It was like what just happened? Because I’ve seen people go to jail for less than that. And then the opposite, Barack Obama. I was five years old. My father told me you can be anything in this world but you will never be president of the United States. Me and my friends used to go to school and joke around, half joking, half serious knowing that that was a truism of being a black person in America. And so to see that? That was also incredible because we were always told it will never happen. It would never happen in my lifetime.

Ivan: Black families don’t tell their children you could grow up to be president. You can go up and work for the president [laughs].

Bjorn: You can do a lot of things, but you will never ever rise to that position. I look at it and I go, sure we can create laws and protest, and now don’t get me wrong, those things are necessary. I think all of it’s necessary, but I think eventually if we really want to create a change that’s long lasting, it’s going to have to be by destroying the system that we currently have.

Lynnette: And also, the onus is not just on those who are oppressed to rise up. The onus is on those liberal white people, those who have privilege, to change their populations, to change those around them. When President Obama was elected, that was awesome, but it also kind of drove in this kind of insidious notion of Well, we’re post racial, don’t you know? And then there is this gaslighting that does happen because just because he got elected did not erase discrimination and racism at all. Whenever people would get up and say, you know, this is wrong, I’m being discriminated against, look at this video of this person being assaulted.

Margarita: And it took videos, because how long had black people been saying they were being targeted by police, and no one believed it?

Lynnette: Right, but even with video, people were like, well, what did he do? What did he do to deserve it?

Ivan: The thing is that nothing has really changed except technology is accessible. Now we can videotape these things. You know, black folks been getting shot by cops for years. The only difference is now we got cell phones that can record it, you know? I mean, that’s the only thing that has revolutionized over the years. Everything else is pretty much the same.

Bjorn: I think as a country we have to finally get to the point where we say the American dream does not exist or that it does exist on the backs of oppressing people regardless, right? Anywhere in this country that there is a millionaire or billionaire, that’s on the back of taking advantage of somebody; someone’s on the bottom that is being oppressed for that one person to be a millionaire. Everybody who grows up in this country has this idea that I’m going to be that. And so therefore in the pursuit of that, it’s okay for all these people to be suffering.

Ivan: There’s a fallacy in this country that makes it believed that everything that they do is somehow for the greater good of the whole. You know what I mean? And that’s where, you know, it gets kinda tricky because who do we consider the whole? Is it us? Is it them? You know, who is us and who is them? It’s not just minorities, immigrants, women, gay, straight, across the spectrum. And we are separated because we live in this society where we pretend to be enlightened, anything that we do is coming from that enlightened point of view. When they were talking about moving Travisville, they said this is for the betterment of the neighborhood, but who consists of the neighborhood? We’re not talking about the people, we’re talking about the real estate, you know what I mean? And that’s where you have that tug of war.

Sheldon: To the question of what it’s going to take to get change, I think of when you see something in the news where they’re like, Oh, so and so is the first black woman nominated or the first black man to be a governor in x, y, z state. Usually it’s followed by “since reconstruction”. Because during reconstruction, there were all these gains that were had because you had the white power structure enforcing that these changes are going to be made across the board. These laws are going to be enforced. And that racism is not the law of the land anymore. And when reconstruction prematurely ended, you had this regression, all of the gains that were made were lost and they haven’t moved a lot of them. We haven’t seen those gains since, which is why you often hear on the news: So and so was the first black x, y, z since reconstruction. So I think in order for there to be some kind of real lasting change, first you have to upend whatever power structure is in existence right now. And that may happen through revolution. But it also could happen because people politically decide it is not the best thing for us as a whole, for us as a country, to have white supremacy be the law of the land, to have people suffer under other people so that they can become millionaires. It’s not beneficial for us as a whole. And if the powers that be decided that we are going to implement those kinds of changes, we’re going to make sure that people have equal protection under the law, and then enforced it. It could take the right government, be it by saying We’re gonna occupy these states. I mean, I don’t know if that’s gonna happen, but I think it would take something as extreme in order for people to go, Okay, these are the laws and while we may not like it, we’re going to get used to it. And then when people get used to it and realize, Oh, we are better, everything is fine, this didn’t destroy our family or our homes, our livelihood, and things like that, then people can go, oh, okay. And then at some point you can take that pressure off from the top down, and hope that people on a community level are going to be there for each other and the law from the top down will protect them. But we don’t have that right now.

Margarita: I’m from Puerto Rico.

Lynnette: Oh! Oh yea.

Margarita: Yeah, so I’m feeling all of this very deeply. Going back to the play, what’s it been like working with the playwright William Jackson Harper and the director Steve H. Broadnax III?

Ivan: They’re horrible people. It was just the worst experience in the world. [laughs] I mean, I don’t know if you could say enough great things about either one of them. Steve, I think I told him not one week or so ago. I was doing a comparison. I remember looking at a documentary once with Michael Jackson and watching him do his thing, you know what I mean? And when you looked at it, you know, put all that controversy and crap away, and just look at the man doing his work. You just knew he was born to do what he was doing. He could not do anything else. And when I watched Steve work, his mind is always going and he’s very meticulous. It’s really great to watch. He’s a great person to work with. He knows what the hell he’s doing. And Will is fun. [laughs] These guys have really creative minds. But I think I just have to say across the board, writer, director cast, I’ve been calling them all rock stars from the very beginning. There’s no weak links in the chain, none at all.

Lynnette: Such joy showing up to work every single day. It’s not even like work. Steve brought that to the table because he says and it’s totally true, he is of service to not only the story but also the actors inhabiting the story, and of service to whatever ancestors are working through it to make it happen. And we just had so much fun in the process of constructing and telling this story. I mean, a lot of it and being in it is not fun, because it is retelling certain things that are horrific, many of which ancestrally you felt. But showing up, it’s like family and I feel like that level of camaraderie in giving, especially doing a script that’s very well written, it’s all right there on the page and the amount of thought and consideration that is given to every line and every piece of every line. It was a true collaboration. Will was open, Steve was open, everyone else was open. And so, you know, even from our table work, it got really passionate but not so much that at the end of it you weren’t walking away smiling. It was really good.

Ivan: I saw that interview where you talked about table work, because it was really something to see. Someone, I can’t remember who, said we got mad but had so much fun getting mad. We were fighting about your character or your lines in the history of what was going on or whatnot. And it was like surgery, where you were watching everybody to kind of dissect, what’s going on here? Why am I doing this? And it was really something to see. And like she said, Steve was really open to letting all of that happen and whatnot.

Sheldon: And they worked so hard. Being that open, that takes work. Yes, it does. Oh, you could very easily say No, we’re going to do what’s on the page, learn the words, say the words, do the actions and let’s do this play, but both Steve and Will were so open to us challenging and questioning the words and the intentions and the actions. We would talk about it. We’d be in dialogue. Will, who’s a very hardworking actor, was abroad shooting a movie during some of the rehearsal process and so he came back for a week and then he had to leave again and then he came back. He was away working on another job and would stay up, you know, with the five or six hour difference, and be writing new pages for us based on the conversations and questions that we had, that Steve would be up all night talking to him about. You know, that kind of openness takes a lot of hard work and I just can’t speak enough to how hardworking these two guys have been.

Margarita: Tell me if you disagree, but to me theater still feels very white and male, and stuck in the past. There’s so much diverse talent out there, but it still feels like a very white, male, straight landscape. Sometimes it feels like we’re making progress, and sometimes it feels like we’re taking steps back, but I’m wondering what your thoughts are and what your experience has been working in theater and what can be done to get to a point where all voices are accurately represented.

Ivan: I worked in the education system for over 25 years, and the arts are not something that’s pushed. It’s one of those things where if a child feels inspired by something, whether it be acting, dancing or singing, then they have to seek it out. You know what I mean? It’s not something that you are generationally teaching the children. It wouldn’t be natural for arts to just appear and I think if you talk about getting more diversity in writing, acting, dancing and all that stuff, you’ve got to start at a base level and that doesn’t start with the adults. The adults have to chart the course, but we have to go to where it begins and then start to bring them up. Teach the arts in the school or whatnot. Nowadays, they say there’s no money in it to teach it, so they take money away from the arts. So you’re not teaching the children that, or anything like that. If you want to make the arts more friendly towards whatever the group may be, you have to start at a place where the creativity begins, you know what I mean? It could be on a junior high school, high school level, but something that promotes the interest and I don’t think interests like that are promoted nowadays. Kids have to go looking for it.

Lynnette: Along those same lines, even if you’re looking at, say an English class. What exactly are you teaching? Which plays? The things we learn or are taught are the pinnacle of theater? We hear Shakespeare. White, dead males.

Ivan: Yeah, that’s exactly what happens.

Lynnette: There has to be an interest in looking at your curriculum to also reflect your students, to reflect your city, reflect your world and open those up and use those as teaching tools as well. And then, you know, if you’re an artistic director or on the board of a theater, if you’re looking around the room and everybody looks like you, you’re doing something wrong. If you’re looking at your entire staff and the only people of color or different sexual orientation are just the people cleaning up for maintenance, there’s a problem there. Are you actually looking at your programming, not just from what’s visible or fashionable— you know, black plays or are really in fashion right now— but what are you trying to do? Are you looking at your mission statement? Does it include everybody? Are you looking at not only what’s going on your stages with the programming you have? Are you engaging with the neighborhood that your programming is in? Who are you serving? When you’re doing audience outreach, are you going to outreach? It’s actually not that hard. Are you going to outreach with lots of other theater companies? Because there are lots of theater companies for lots of people that do programming specifically focusing on all artists. Are you aligning yourself with them? Are you going to see things? Are you looking at all of the immense talent that is in the city, or are you just towing the line and getting paid for that? And if you are, I say make that a choice. Say that you are, but don’t say that we are a theater for everybody and then turn around and just be the same old, same old. I think that it’s necessary for boards of theater and artistic staff to actually be very real about who is making those decisions and the different perspectives that they are getting in. Even your costume designers or set designers, sound designers— there are lots of people from very diverse backgrounds. There’s actually several excel sheets with lists. So if you don’t know, there are people that you can seek out. And if you say that there are none, then that means you’re actually not doing your job.

Sheldon: I think that the power structure has to evolve because you look at a lot of the theater institutions, and sometimes the plays are more reflective of society than it is of the administrators in the field. And while that might be good, it makes me question what are you actually seeking to do with these plays? Because on one level you’re bringing people in. Letting them feel good, like another one of those liberal pats on the back. We feel good because we produced this, because we told this story, but who is the audience seeing the story? Who was actually consuming this? Who are the people who are deciding this and why? That’s why I feel like sometimes I go to the theater and I see like torture porn for minorities. Like, I can cry for people and it makes me feel better because it made me see that I see their humanity. But do you see their humanity in your daily life? Do you see their humanity and what you’re doing? And does the theater see their humanity? I think it comes down to our blind spots and our consciousness. For example, me walking through the world as a black man, I have this double consciousness, so to speak, of what it is like to walk through the world as a black man. But I also know, because I have to navigate a world where black people are not the ones making the decisions, I have to navigate a white world. So I’m aware of how I move through the world. If I didn’t have that double consciousness, I would be blind to some of the things. I’m not a woman. So walking through the world as a man, I don’t see some of the things that women see. I have privilege, I benefit from it. I just go on the subway sometimes and I don’t think. A friend of mine, she was like Will you actually just take a cab with me? It was something I didn’t think of, I was just like, Oh yeah, we’ll just take the train together until this point. And we split. She was like, I’d rather, you know, get a cab together. And it was something I hadn’t thought of, but she thinks of daily, you know? So if you are in a position of power as a theater administrator and your blind spots aren’t being covered by either you doing your homework and your research and figuring out why it’s important to do certain works and why it’s important to have other people working alongside you, then you’re not fully doing what your job should be, and you either need to make room for someone who is going to do that or you need to make sure that the people around you are holding you accountable.

Ivan: I think at the end of the day, a revolutionary thing as a matter of thought and action takes us out of our comfort zone and nobody wants to be out of their comfort zone. Whether you’re white or you’re black or someone like that, the only way that you grow in anything is to come out of that. It’s a little difficult but that’s the way change works universally.

Bjorn: I just think that, same with this country, it needs to change from the top. We can surround ourselves with people, but at the same time, the theaters I’ve seen work well are the ones that were run by people of color or women and because they naturally tried to look at the whole. We also have to talk about, yes, stories get done, yes, but it’s always done from the white gaze anyway. So are these stories really challenging the norm? Is it really something that’s gonna push the community forward and open eyes? That’s something that always makes me think.

Stori Ayers (Bethany/LaVerne) is elated to make her EST debut. Acting credits include: A Raisin in the Sun (Indiana Repertory Theatre & Syracuse Stage); Foster Mom (Premiere Stages); Detroit ‘67 (Chautauqua Theater Company); Barbecue (Pennsylvania Centre Stage); Jitney (Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park); Yellowman (Anacostia Playhouse); Blood at the Root (National Black Theatre); Father Comes Home From the Wars Parts 1, 2 and 3 (Round House Theatre); Doubt; Love’s Labours Lost; In the Red and Brown Water (Pennsylvania Centre Stage). Stori will next be seen as Black Mary in Gem of the Ocean at Round House Theatre.

Denny Dale Bess (Gillette/Honeycutt) is honored to be a part of Travisville. Theatre: The Legend of Georgia McBride by Matthew Lopez (regional premier, Dorset Theatre Festival), Year of the Rooster by Olivia Dufault (world premier, EST), The Sluts of Sutton Drive by Joshua Conkel, Where the Children Are by Amy Fox, and Phantom Killer by Jan Buttram (world premier). Film: How He Fell in Love, The Suspect, The Umbrella Man, My First Miracle, and Darcy. TV: “Law & Order”, “Law & Order: Criminal Intent”, “Public Morals”, “Boardwalk Empire”, and “The Blacklist”. He lives in Hell’s Kitchen with his beautiful wife Abigail. Represented by Andreadis Talent Agency & Stewart Talent NYC. Member of AEA, SAG-AFTRA, & EST. Thank you to EST. WJH, you are a man of passion, perseverance, and talent. Thank you sir!

Sheldon Best (Zeke Phillips) Theatre Credits include: Sugar in Our Wounds (Manhattan Theatre Club), Romeo & Juliet (Public Theater, Classical Theatre of Harlem), brownsville song: b-side for tray (Lincoln Center/LCT3), The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (Atlantic Theater), the box: a black comedy (Foundry Theatre), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (CTH), Freed (59E59 & Penguin Rep), Six Rounds of Vengeance, Alice in Slasherland, Geek! (Vampire Cowboys); Soul Samurai (Ma-Yi Theater & Vampire Cowboys), Paradox of the Urban Cliché (LAByrinth). TV/Film – “Manifest” (NBC), “The Good Wife,” “Unforgettable,” “Person of Interest” (CBS); Ghost Light (H9 Films). www.SheldonBest.com.

Brian D. Coats (Elder Alden Hearst) Broadway: Jitney. Off-Broadway includes: La Ruta (Working Theater), The First Noel (Classical Theatre of Harlem/The Apollo), On the Levee (Lincoln Center), The Merry Wives of Windsor, Two Gentlemen of Verona (Public/NYSF). Regional: The Royale (Cleveland Play House), The Nest (Denver Center Theatre), Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (Huntington Theater, Studio Theatre DC), Seven Guitars, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (Two River Theater), Fences, A Raisin in the Sun (Geva Theater), Distant Fires (People’s Light and Theater), Clybourne Park (Caldwell Theatre), The Wedding Gift, pen/man/ship (Contemporary American Theatre Fest), Count (PlayMakers Rep). TV includes: “Law & Order”, “Law & Order: SVU”, “JAG”, “Blue Bloods”, “The Sopranos”, “Boardwalk Empire”, “Luke Cage”, and “The Blacklist”. Up next: King Hedley II.

Bjorn DuPaty (Min. Ora Fletcher) Off Broadway: Mlima’s Tale (Public Theater), Two Mile Hollow (Women’s Project Theater). National Tour: Julius Caesar, Comedy of Errors (The Acting Co.). Regional: Do You Feel Anger (Humana Festival), A Raisin in the Sun (Crossroads Theater), Clybourne Park (Pittsburgh Public Theater), Fairfield (Cleveland Playhouse). Film: Demolition TV: “Alpha House”, “Sleepy Hollow”, “The Blacklist”, “Person of Interest”, “Zero Hour”, “All My Children”. MFA From Rutgers’ University, Mason Gross School of the Arts. http://www.bjorndupaty. com

Lynnette R. Freeman (Georgia Dawson) is beyond excited to be working on this fantastic play with this fiercely talented group of artists at her EST home. Lynnette is a Jamaican-American actress, dancer, and teaching artist, raised in East Cleveland, OH. Brown/Trinity MFA. Member of EST, and the League of Professional Theatre Women. Previous EST roles: Letitia in On The Outs, Amy in Kentucky, African Woman in Waking Up. Other roles include God in An Act Of God, Ruth in A Raisin in the Sun, Reheema Abu-Salaam in In a Daughter’s Eyes, Esther Mills in Intimate Apparel. Special thanks to friends and family for always believing, encouraging, and supporting. LEAP!

Nathan James (Gunn) is excited to be making his debut with EST! Off-Broadway: Playing with Fire (Gene Frankel Theatre), Black Angels Over Tuskegee (St. Luke’s Theatre). NY: Maid’s Door (Billy Holiday Theatre), Growing Pains (One man show, Billy Holiday Theatre). Regional: Pennsylvania Centre Stage, Pittsburgh City Theatre. Film/TV: “Shades of Blue” (NBC), “Quantico” (ABC), “The Wire” (HBO), “Blindspot” (NBC), “VINYL” (HBO), “Person of Interest” (CBS), “The Interestings” (Amazon), “Blue Bloods” (CBS), “The Path” (Hulu), Pain Within (Sundance Film Festival), We Are Unsatisfied (opposite Billy Crystal–Post- production). BA: Pitt MFA: Penn State. www.officialnathanjames.com

Ivan Moore (Mims/Birch) is a Native Brooklynite, who is grateful, honored, and thrilled for the opportunity to work with Ensemble Studio Theatre. Ivan’s acting career began at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. He continued his education at CCNY, where he received a BFA in Theatre and Acting and continued his studies at the William Esper Studio in New York City under Bill Esper. His recent theatre credits include The Cost with The Negro Ensemble. Recent Film and TV credits include roles in the award-winning short film Blue Diamonds and “Luke Cage” (Netflix), “Bull” (CBS), & “Gotham” (Fox).

Shawn Randall (Beasly/Orthel) is an actor, poet, singer-songwriter, musician, freestyle emcee, and producer, born and raised in Brooklyn. He is the founder and host of Symphonics Live, a multi- disciplined evening that showcases the finest singer-songwriters and poets in NY, currently in residence at The Bowery Poetry Club. Shawn has competed in the National Poetry Slam and performed with the Blue Man Group, Ensemble Studio Theatre, Public Theatre, the Bardavon Opera House, The Kennedy Center, INTAR Theatre, La Mama, and Brooklyn Academy of Music. http://www.iloveshawnrandall.com