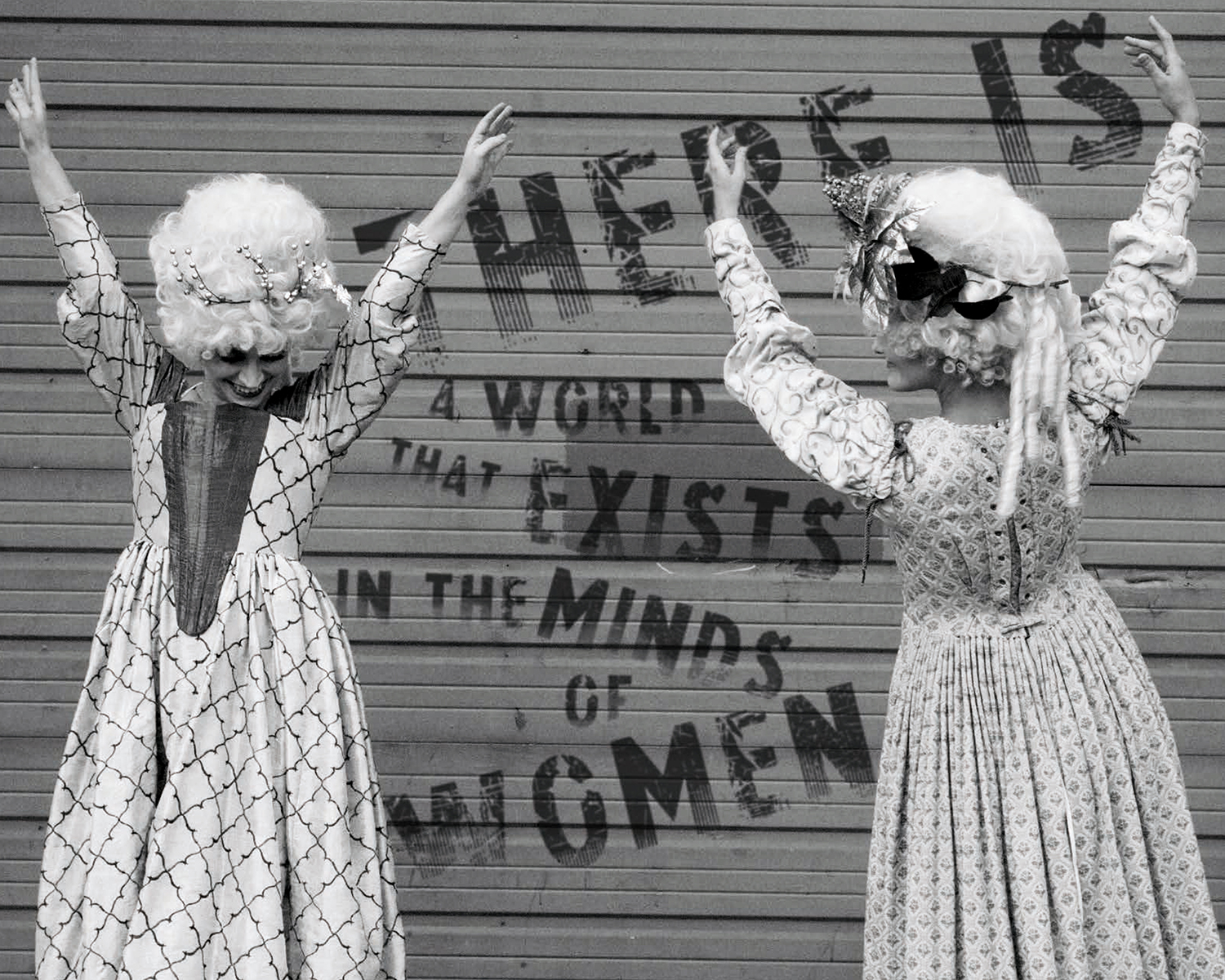

When you think of plays that empower women, The Taming of the Shrew doesn’t come to mind, but Chicago Shakespeare Theatre’s new production is trying to change that. With a cast of thirteen women and a suffragette twist, this Shrew is unlike any production you’ve ever seen before. I sat down with three of the show’s stars, Crystal Lucas Perry, Alexandra Henrikson, and Olivia Washington to talk about voting, feminism and Oregon Trail.

Kelly Wallace: So, you guys have started performances? You started last week, yeah? Let’s start with who you are and who you’re playing—just give me a short description of that character.

Crystal Lucas Perry: I’m playing Petruchio as well as Mrs. Van Dyne—Victoria Van Dyne. Mrs. Van Dyne is a suffragette during 1919, and one of the champions of the club. She prides herself on being out and physical with the movement and doing her best to do her part. Any chance she has to express her enthusiasm for the cause and the rights of women, she takes it. She encourages her other suffragettes and members to also take pride in the cause. And then Petruchio, obviously the tamer of the shrew, he’s a man going after what he wants. He will stop at nothing to obtain that.

Alex Henrikson: Hello, I’m eating a muffin. When I know I’m being recorded I suddenly get real weird and I apologize. I’ll stop trying to entertain. I play Kate and Mrs. Louise Harrison. What’s so fun is Mrs. Louise Harrison is a woman in 1919 and is an industrialist’s wife and is happy to be so and likes that her husband is in charge. I like to imagine him as a middle-aged Sean Connery…

Crystal: Wouldn’t we all like to imagine being married to a middle-aged Sean Connery?

Alex: Sean Connery’s where you start. No, but, she’s that woman who has learned to play the world with the set of tools that she has in 1919 to have power, which is her beauty, her being a great host, her gentle voice, and also her diva-level narcissism—which is another part of it that’s a little hard to reconcile sometimes. She doesn’t understand suffrage. She’s come here to act; she wants to be an actress. I think she’s a frustrated actress because she would’ve been a great actress in a different time. Then I get to play Kate, which is just the most fun. It feels like every time we get together is a political act, which feels great at this moment in time. In the beginning, I get to be a woman who goes from being a wildcat and not knowing how to use her words exactly but having all this passion, to a woman who figures out how to use her words by the end. Unfortunately, what she uses her words for is not what me, Alex Henrikson, would want her to stay. That’s what the play wrestles with on that journey.

Olivia Washington: I play Emily Ingersoll slash Ms. Ingersoll slash Bianca. Emily is a daughter of the Senator, Senator Sherman, and she’s very loving and supportive and keeps to herself. She has an awakening at the end, and meeting all these women … she’s not an initial supporter of suffrage, but she’s educated on it. She’s learned it more in a book way, not in the way of having seen what it is. So I think she wakes up to the idea of what it means to believe in something, and believe in something for the country and for herself as well. She’s able to have conversations with her mother that she wouldn’t have been able to have without that awakening. And then Bianca … she’s so much fun to play. And in a similar way, she is a loving daughter. But she kind of uses her power in a different way than Kate uses her power. She picks her times to speak and how she speaks to get what she wants, but then still goes behind her dad’s back and gets married. I like that kind of sassy, quiet, sneaky way about her.

Kelly: What does it feel like to do a show, which as you mentioned has this political side, right now? This is, undeniably, a very contentious moment in our country, no matter what side you’re on.

Crystal: Well, I think about the Women’s March that happened everywhere, I like to imagine Mrs. Van Dyne at the front lines of that march, making all the hilarious yet powerful signs. I can’t help but think of her as one of those women, and the Instagram photos she must have taken [laughter]. That was a day to gain a ton of followers. But, really, that’s the beauty of what I get to witness. I watch how these women choose to fight, seeing how the women of today choose to fight, or choose to push against the barriers we’re facing. It always seems to be the same. They use what they have to get what they want. They take the opportunities that they are able to seize and use that as a platform.

During the play, we have our own “votes,” um … what’s it called?

Alex: A democratic process? [laughter]

Crystal: We do the whole voice voting “ay”/”nay” thing, and that’s what’s so beautiful. This is a chance where we get to demonstrate and recognize our power. It might be something meaningless, but it means something to us. We can make change within our little house and that gives us the power to go and make change elsewhere. That’s something I like, the parallels between those two, of how we choose to fight and how we energize ourselves to make something better.

Alex: Yeah, what you just said made me think of how being in high school, there were lots of boys telling me like, during the Gore vote (okay, it was a little past high school, don’t worry about the time), that my vote didn’t mean anything, that it was the lesser of two evils.

Crystal: Where’d we hear that again?

Alex: Exactly. It comes up every single election, doesn’t even matter who the politicians are, there’s a mistrust of government. To me, I never saw it as a lesser of two evils. I always can see someone I admire, some quality, and only this year—and it’s taken me a long time to get here—but my vote does matter. What I think does matter. I went to the Women’s March and I saw a lot of little girls with a lot of women around them saying, No, this is important. There are more women getting involved in politics. When I was doing research for this show, I read Rebecca Traister’s book, All the Single Ladies. She tells this story of women in Wyoming, where there’s all this trash in the streets and the male politicians and the mayor couldn’t get it together, and the women were like, “Our streets are disgusting.” So they all ran for positions in the town, won, got all this shit done, and then went back to the house all like, see you later. There’s part of me that’s really excited. For me, this has been a huge awakening experience, and I think the same happens for my character, and getting to do The Taming of the Shrew for the third time (I’ve played Gremio and Bianca before) … what’s been nice about this time and this rehearsal process is when we would get to points where it just was never okay with me. You watch these versions and you’re like “…and he probably raped her,” or he’s calling her chattel. It’s dark. It’s so funny, but then it gets really, really dark. You see these two characters smash against each other and fall in love.

Kelly: Not the fun Beatrice and Benedick kind of thing.

Alex: They’re literally hitting each other.

Kelly: It isn’t that contentious, Shakespearean, comedic courtship…

Alex: It’s their way of falling in love, and I think they do fall in love, but for me as a modern woman in 2017, playing a woman in 1919, watching this play from the 1590s, I have all these out of body experiences. I’m seeing what’s not okay with me; I’m seeing where my line is. I think that now, as a woman who is 32 (and you can print that, I’m proud of it), I’m finding all these things that aren’t okay for me anymore. I can point to that and say it wasn’t okay when it happened.

Olivia: I agree with both of them. To put it so simply, it’s amazing how something so small can birth a bigger movement. I think that was a lovely reminder, not just in this political climate, but in the world. This story of these women, it shows your voice matters, even if people are telling you it does not matter. If you can just get involved, I think that’s what most people of our generation are saying right now. Most millennials are like, you know what, a takeaway from this whole election is that I need to pay more attention to what’s happening. We have to take back our rights, and our voice, because we can. I’m going to educate myself on things about our government that I let go by, because I let people speak for me, or because I assumed it would be okay. Growing up in that way, we have to take responsibility for our actions and our part in making a difference in the world today.

Crystal: And what affects one affects us all. Mrs. Van Dyne knows the passing of this, this 19th Amendment, and the right to vote, may not mean mountains are moved for her individually. A move for women is a move for her. A win for women is a win for her. Not until ’65 when the Voting Rights Act passes does she get that, so the barriers are still in the way for her character particularly. But the fact that they’ve been able to come together and be united in this is a complete reflection of what I see with women today. We have been able to set aside our differences and our viewpoints because at some level, we agree this vote is a right that belongs to us all. `

Olivia: For the good of the country.

Kelly: You’ve had a few performances—do you have any sense of how the audience has been reacting? It’s a show that everyone’s familiar with, but has a wildly different take on.

Olivia: I’ll speak up first since they’re onstage most of the time and we’re in the aisles watching it. It’s one of my favorite parts, watching the end of the first act. They get married, and you’re just listening to the audience respond. Everyone is so sucked in. They’re trying to figure out Petruchio like, is that a woman? I don’t know…

Alex: Crystal is an incredibly convincing gentleman…

Olivia: But really, you watch this man overpower this strong-willed woman and what is she gonna do? What are we gonna do? Can we do anything? The vocal responses coming from the audiences are chilling sometimes. So it doesn’t matter if it’s a man playing this part; it doesn’t matter if it’s a woman. If you’re good at your job, you get the message across. They do it so beautifully and you’re watching it and … it sucks. People realize it’s not that kind of comedy.

Alex: And that final “No,” Barbara [Gaines, Artistic Director] was like, “What do you feel in that moment?” And my answer was: “I don’t want to go with him.” So she told me to say that. And I did. And you hear the audience laugh, it’s like this almost impetuous child. Then Crystal takes that impetuous energy away and everyone is silent. I love this play, and I am a feminist, and this is the moment for me that shows why this play is so tricky.

Kelly: How is that for you, playing such an aggressive man? Does the gender swap change anything about your onstage interaction?

Alex: I feel like I’m actually stronger onstage with her than with any male counterpart because I feel like she can actually match me. Like, as an actress, I’m very tall. I’m 5’10” and I have a very large wingspan and a very big voice. Oftentimes, I felt like I had to diminish myself to make sure the guy looked strong, or at least that’s the traditional gender role. So many shows would say they couldn’t find someone to match me, which, I think, is often code for finding someone as tall as me. When I met Crystal, it was like wow, it’s on. I’m not pulling any punches, she didn’t pull any punches with me. We just kept raising up. I wish every actor could get to work with Crystal Lucas Perry and Olivia Washington at some point. Everyone says yes. No one is diminishing themselves. Now that I know how much power there is, I can see how I wasn’t raising up to that.

Crystal: Aside from the physical adjustments I’m trying to show that are more masculine, I honestly don’t turn off my female brain. I really think of him as a woman who thinks differently and who executes from a different place than my other counterparts. As a woman playing this role, it’s incredibly satisfying because I know every move I would make as a woman. I know every tic that would turn me off or on as a woman. So because I know those things, I get to decide if I would be turned off or on by that.

Kelly: You know to push those buttons.

Crystal: Oh, I get to push the buttons, and I recognize when buttons are being pushed of mine. It’s really lovely and working with Alex has been fun because she does not filter and she goes all in and so we’ve been able to take this scene … I mean, we could show you the wooing scene in a million different ways and keep you on your toes. That’s just been the joy. Previews are helping us figure out what story we want to tell with that. At the end of the day, it’s two people coming together and realizing they can’t just break through the other person, they can’t just go around them, they have to meet—there has to be a collision. It’s exciting. He’s a really strong woman, strong in a different way.

Kelly: Now, the framing of this show is the suffragette movement; you’re all playing these 20th-century suffragettes as well. You’re both people of color, as you brought up, the right to vote wasn’t a “win” at that moment, so what is that like for you as a human and as an actress? This victory, ostensibly, has happened, but not for everyone.

Crystal: A win for one of us is a win for all. And we talked a lot about that. We chose to acknowledge who we are in the space and celebrate that, because that’s one more beautiful thing about these women being able to come together because of their social level. They’re here, in this group, choosing to commune with this Shakespeare. Of course, all of these things happen on this day. I think that I’ll speak for Mrs. Van Dyne: she’s a woman who has a vision for the future, and she is able to see that we have to focus on right now, and right now, this is the next step. This is the opportunity. Similar to how Petruchio seizes an opportunity when it’s presented, she’s gonna seize this opportunity as it stands before her. There’s not many times we have to touch on it. It’s there. It’s a part of the play by us being onstage.

Kelly: It doesn’t need to be explicit.

Olivia: It’s underneath; the undertones are there. And we have different perspectives. You have Mrs. Van Dyne, who is such a clear cut fighter for the cause, and I think for my character, I was raised by a white Senator’s family, so I come from a place of privilege in that family and in that home. And yet, there’s this kind of … Oh, I have to start using my voice in a way outside the safety net of my home that was created for me. I am a woman of color in this world, and I want to effect change in this world, but not just from back here. So, how do I step forward? This is all undertone, of course.

Kelly: But that’s the kind of undertone and tension that keeps the show interesting, it draws you in even further.

Crystal: There’s a moment in the play where some of us rush out to join a rally and some of the women stay, and you hear some of their reasons. Some people feel they’re too old, some are too afraid, and you get a chance to see that it’s not just because they don’t want that, it’s because they have something to lose themselves. So getting to the core, stripping color, stripping social class, stripping all of those other things, it gets to the human need of wanting to be safe and wanting to make change and wanting to be a part of something great.

Olivia: It’s human. You see throughout history—no matter race, gender, whatever—to fight for a bigger cause, you let go of yourself, it’s for the bigger battle.

Crystal: And I don’t think these women are done. I feel like they’ve got a taste of change and the ability to make change.

Kelly: There’s an optimism in where it ends up. The “tide-turning” feeling is very present. And that one-hundred years ago … not even, really…

Olivia: It’s so crazy!

Kelly: How recently all of this was for millennials is mind-boggling. The Voting Rights Act, Roe vs. Wade, marriage equality … we feel like these are all a given. Of course, we should have those things. I think the good idea behind the Women’s March is maybe to remind younger generations how much there is to protect, and what we still have to lose.

Alex: I was born in the ‘80s, we had the internet, I was playing Oregon Trail on it…

Kelly: I’m not sure if the internet was a net positive or not yet.

Alex: I’m not sure either, we won’t take a side. But part of it was that I saw all this heroines in Disney movies. I wasn’t seeing Snow White anymore, I was seeing Belle. And she really liked reading. Then it turned into this competition of reading. Or She-Ra princess of power! I think the heroines and the storytelling I had growing up versus what my mother had … it affected what her expectations of me were. She told me if I got pregnant before 30 it would hurt more to give birth to the baby? Which is a lie, of course? She also told me I didn’t need to learn to cook, let’s look into writing more. I think she was doing this very active “you will not be that woman.” By ‘that woman,” she meant the idea of what she was brought up as, and what she was trying to steer me away from. By now we know every woman is every woman. I love cooking. I get turned on when I cook a meal for a man. It is hot! You know? I also get turned on when I cook a meal for all my friends, not turned on in that way. It’s just seeing all the different options that we as women have. When I look at Mrs. Van Dyne and I see her going outside and going into the fray again, I think she is black, she will get double hurt and that’s how brave she is. That’s one of the things I use for my character to move forward. She’s such a brave fucking woman, why am I being a coward over here? You can’t know something until you know it. Because I’m playing Kate, I have a very clear journey through the play of learning that there’s more. And once you know something, you can’t unknow it. I think that’s what’s so exciting about the storytelling in this. I think that our storytelling is powerful—what story we are telling, specifically.

Crystal: I definitely have to thank Barbara Gaines and Ron West, our writer and director, for allowing us the time to work through this process. We have a huge play to learn, we didn’t have that much time to do it. We also have two plays to learn, because of the frame of a play within a play. It’s still being developed every day. So to be able to alot for those times where we can have these conversations as we’re having now, and be very specific and clear about the weight of these situations and the way we want to play these things here—it’s a balancing act. Truly, knowing the mothers who have come before us and all of their accomplishments and their sacrifices and their triumphs … all of that is what lies beneath the foundation of this play.

Kelly: What do you hope the audience experiences with this show?

Crystal: Always, for me, I hope it starts conversation. I think there are so many things to talk about after you see this show. Whether it’s about how you had so much fun watching these women…

Alex: It is funny, it’s really funny!

Crystal: Thirteen women onstage at one time. We were just talking about how we’re pretty sure there isn’t another production with thirteen women onstage in America right now. That’s a beautiful thing. All of these characters would be men. So there’s a celebration of that! There’s a celebration over these women playing a part in the 19th Amendment! But also Alex’s character’s journey—not just as Kate, but as Mrs. Harrison—is that she goes through a change. One of her lines is “people change” and again, it’s also what Olivia says. The more we educate ourselves, the more information we have about what is happening and what we can do to be a part of that—how we’re hurting, and how we’re helping. You could say the same about the environment: ultimately, the more we know, the more we can contribute. I believe that everyone who comes to the theater wants to be a part of something.

Olivia: Also, I hope the audience sees how things aren’t so black and white. Growing up in our safe millennial bubble, we have to realize things can be confusing and muddy. It won’t always be all good or always bad. Coming away from this production, I’ve laughed, but there are other parts I’m not really okay with. Why is that? You have to realize the world is not so clear-cut, so where do you fit into that? How do you have a conversation about that? I think that’s what I come away looking at.

Crystal: You’ll meet this women and see little glimpses of who they are and their backgrounds— whether it be religious, or racial, or a stance—but no matter what, they’ve come together for this cause. No matter what they are, there is something bigger than them. For the audience to see that, to see it was happening during that time, and to have it mirror what’s happening now—to know it’s possible, it still exists, that things do matter. It’s an important reminder for people.

Alex: I like looking out into the ground. One night, I was doing the final monologue. I saw this woman elbow her husband at a certain point. I guess I want women to feel seen. I hope men can see their women feel seen and support women talking. It’s just an opportunity to say hi, we see you. There’s one moment where Barbara had given me the direction, to be Kate at the end and do the submission speech, but let Mrs. Harrison push against that. I almost felt like I saw ghosts last night. Because there are posters of suffragettes, but then I saw my mother, and my grandmother, and little me, and the little mess of people in the audience, and their mothers and grandmothers—and I’m wearing my grandmother’s ring in this, so it feels like these generations of women who have supported and loved each other. There’s something beautiful about women from 2017 playing women from 1919, playing men from the 1590s. You feel the ghosts. Theater is a tradition where you feel the ghosts anyway; you feel this communal, tribal vibe of coming together to tell a story at the end. There’s this moment of the campfire and our mothers and our grandmothers holding hands across millennia, and it’s beautiful.

Crystal Lucas-Perry makes her Chicago debut at Chicago Shakespeare Theater. Off-Broadway credits include Bull in a China Shop (Lincoln Center Theater); Little Children Dream of God (Roundabout Theatre); Bastard Jones (The Cell Theatre); The Convent of Pleasure(Cherry Lane Theatre); Storm Still: A King Lear Adaptation (Brooklyn Yard Theatre); Devil Music (Ensemble Studio Theatre); and The Wedding Play (The Tank Theatre). Regional credits include A Sign of the Times (Goodspeed Musicals); Far from Heaven, A Streetcar Named Desire, Finding Robert Hutchens, and When You’re Here (Williamstown Theatre Festival). Film credits include Mimesis 2, Frank and Azalee Austin, and Roulette. Ms. Lucas-Perry is also a solo artist and continues to compose, produce, and perform her original music at venues across the country. She received her BA from Western Michigan University’s College of Fine Arts and her MFA from New York University’s Tisch Graduate Acting Program.

Alexandra Henrikson makes her Chicago debut at Chicago Shakespeare Theater. Broadway credits include Larry David’s Fish in the Dark and The Snow Geese (Manhattan Theatre Club). Off-Broadway and her off-off Broadway credits include: We Play for the Gods (Women’s Project Theater); Bones in the Basket (The Araca Group); Hell House (St. Ann’s Warehouse); Commedia dell’Artichoke (Gene Frankel Theatre); The Maids (Impure Artists); and Much Ado About Nothing (Smith Street Stage). Her independent film works include: Towheads, Love Like Gold, and Here We Are in the Present … Again. Regional credits include: the world premiere of Steve Martin’s Meteor Shower (The Old Globe); Ironbound (Helen Hayes nomination, Round House Theatre); Fairytale Lives of Russian Girls (Suzi Bass Award – Best Ensemble, Alliance Theatre); and productions with California Shakespeare Theater and the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center. Ms. Henrikson received a BFA in theater from New York University and an MFA in acting from Yale University.

Olivia Washington makes her Chicago debut at Chicago Shakespeare Theater. She has appeared off Broadway as Laura in The Glass Menagerie (Masterworks Theater Company) and in Caucasian Chalk Circle (Stella Adler Studio of Acting). Her regional credits include Clybourne Park (Hangar Theatre). Film and television credits include Lee Daniel’s The Butler and Mr. Robot. Ms. Washington received her BFA in drama from the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU.

Lissa Levin is the recipient of the prestigious Kleban Award for her libretto for Twist Of Fate; composer, Ron Abel. The musical comedy won L.A. Weekly’s Musical of the Year and two L.A. Drama Critics Circle Awards, and a Los Angeles Ovation Award nomination for Best Musical. Her play, Sex And Education, first presented at the Kennedy Center’s Page-to-Stage Festival, (New York premiere, Penguin Rep), opens in spring of 2016 at the Laguna Playhouse. She also penned book and lyrics for Jewsical, The Low Bar Mitzvah; Hot Blooded, A Vampire in Rio; and the play, What Would Jesus Do? A twenty-five year veteran of television as a writer producer, Levin’s credits include the Emmy Award winning Mad About You and Cheers; Wkrp In Cincinnati, Family Ties, Brothers, Complete Savages (with Keith Carradine), Thunder Alley (with Ed Asner) and Gloria (with Sally Struthers), amongst many others. Her essay, Pisser, a rant about insufficient stalls in women’s restrooms in theaters, was published by Random House in an anthology of noted female humorists: Life’s A Stitch; later transformed into a theatrical revue co-produced by Levin, a staunch activist, benefiting breast cancer research.

Lissa Levin is the recipient of the prestigious Kleban Award for her libretto for Twist Of Fate; composer, Ron Abel. The musical comedy won L.A. Weekly’s Musical of the Year and two L.A. Drama Critics Circle Awards, and a Los Angeles Ovation Award nomination for Best Musical. Her play, Sex And Education, first presented at the Kennedy Center’s Page-to-Stage Festival, (New York premiere, Penguin Rep), opens in spring of 2016 at the Laguna Playhouse. She also penned book and lyrics for Jewsical, The Low Bar Mitzvah; Hot Blooded, A Vampire in Rio; and the play, What Would Jesus Do? A twenty-five year veteran of television as a writer producer, Levin’s credits include the Emmy Award winning Mad About You and Cheers; Wkrp In Cincinnati, Family Ties, Brothers, Complete Savages (with Keith Carradine), Thunder Alley (with Ed Asner) and Gloria (with Sally Struthers), amongst many others. Her essay, Pisser, a rant about insufficient stalls in women’s restrooms in theaters, was published by Random House in an anthology of noted female humorists: Life’s A Stitch; later transformed into a theatrical revue co-produced by Levin, a staunch activist, benefiting breast cancer research.

Bear Bellinger is an actor, writer, singer, bartender, activist, and all-around trouble maker based in Chicago.

Bear Bellinger is an actor, writer, singer, bartender, activist, and all-around trouble maker based in Chicago.