To hear some people tell it, New York is the only incubator for the most exciting young artists. But as the Sharon Playhouse proves, creating work outside of the Broadway and Off-Broadway sphere isn’t just a way to pay the rent — it’s a way to make the art you really want to make.

We took a break from the city and met with Johnson Henshaw, Artistic Director of Sharon Playhouse, and director-in-residence Morgan Green after their first run-through of The Music Man — their third collaboration this summer — to talk about the inventive restructuring of the Playhouse’s season, the importance of trust, the goal to foster emerging theater artists, and their thoughts on the future of this art form.

Michelle Tse: How was the first run-through?

Morgan Green: It was good. I have a headache [laughs] but it was really good.

Michelle: Should we get you some water?

Morgan: I’m good. I just had some; I’ll be okay. [laughs] No, but it was very exciting to see everything together. Johnson was there, and we had the smallest little audience so I feel like there was a lot of pressure in a good way, so that the actors were really focusing.

Michelle: That’s good. That’s exciting! So I wanted to start with asking about why you, Johnson, chose to do a director-driven season, particularly with an emerging female director.

Johnson Henshaw: I’m a director myself, and in my 20’s all of my playwright friends had so many opportunities for fellowships and mentorships and all sorts of ways that theaters in New York were trying to connect with them — they were trying to foster and incubate them. There’s not a lot of that for directors. Then I did this fellowship with the Old Vic in London. I went over to London, and visited many of the major theaters there — the National Theatre, the Donmar. Those theaters have these incredible incubators where they take young directors who have just gotten out of drama school or university and they start giving them space and time and money — they’re fully salaried! — and they start prepping them so that they are ready to do mainstage productions at the National Theatre when they’re like 26 years old. So then those directors are being seen by commercial producers and other artistic directors. Their work is getting seen much earlier and their careers are so much more dynamic and fruitful because of it.

Directors in New York have to tie themselves to playwrights. They have to really fight for those relationships. [Morgan and I] talked about this a little bit. The playwrights you get, that’s how your boat floats or sinks. It’s so often that the director’s work takes a back seat. When I had this opportunity, I was like, This should be a place that’s a theater for directors. Where they get to come up and do work that they’re excited about, as opposed to an artistic director being excited about [a certain] play, and finds a director to do that work.

I wasn’t sure originally that it was going to be all one director for the whole season but I had reached out to people at Playwrights Horizons, the Public Theater, Manhattan Theatre Club, and New Georges, and I said, Who are young directors you’re interested in? There was a bunch of names on each of those lists, and some people were on two lists, but maybe not all of them, and there was only one name that was on every single list, and that was Morgan’s. I actually didn’t know her work. I didn’t know her. [laughs] This was all happening around late December, and Minor Character the show that Morgan did with [her theater company], New Saloon, had been asked to be in the Under the Radar Festival as part of the Incoming lineup.The show was sold out, but I got a friend of mine to write Morgan to say, Hey, this is my friend Johnson, he just got this job, he wants to come see your show, can you get him in? And she said yes, of course.

I thought I would go see Minor Character, and if I liked it, I’d be like, Why don’t you direct a show this summer? What show do you want to do? And I was so blown away by it, it was so incredible, and one of the best things I’ve seen in the theater ever, I couldn’t believe it. And the ways in which it was great felt like the work of a really great director. It was so smart and so stylish and moving. So I met with Morgan, we had breakfast, and I sort of was like, Will you come and direct all the plays? Because first of all, I wanted to bring Minor Character here, but I didn’t want that to be the only show that Morgan directed this summer. Selfishly, the best part about this job, is I get to program work that I want to see. It’s the best part of being artistic director.

Because this audience is an older audience, the work that has typically been done here at the Playhouse is very traditional and I was trying to figure out what were the programming choices that would be great for a director to tackle but for this audience would feel welcoming. So my guidelines were a classic American musical, a classic American play, and a new work, and that was Minor Character.

Michelle: So Minor Character kicked off the season for obvious reasons that Johnson just touched on, and tonight we’re seeing Far Away. Why Far Away?

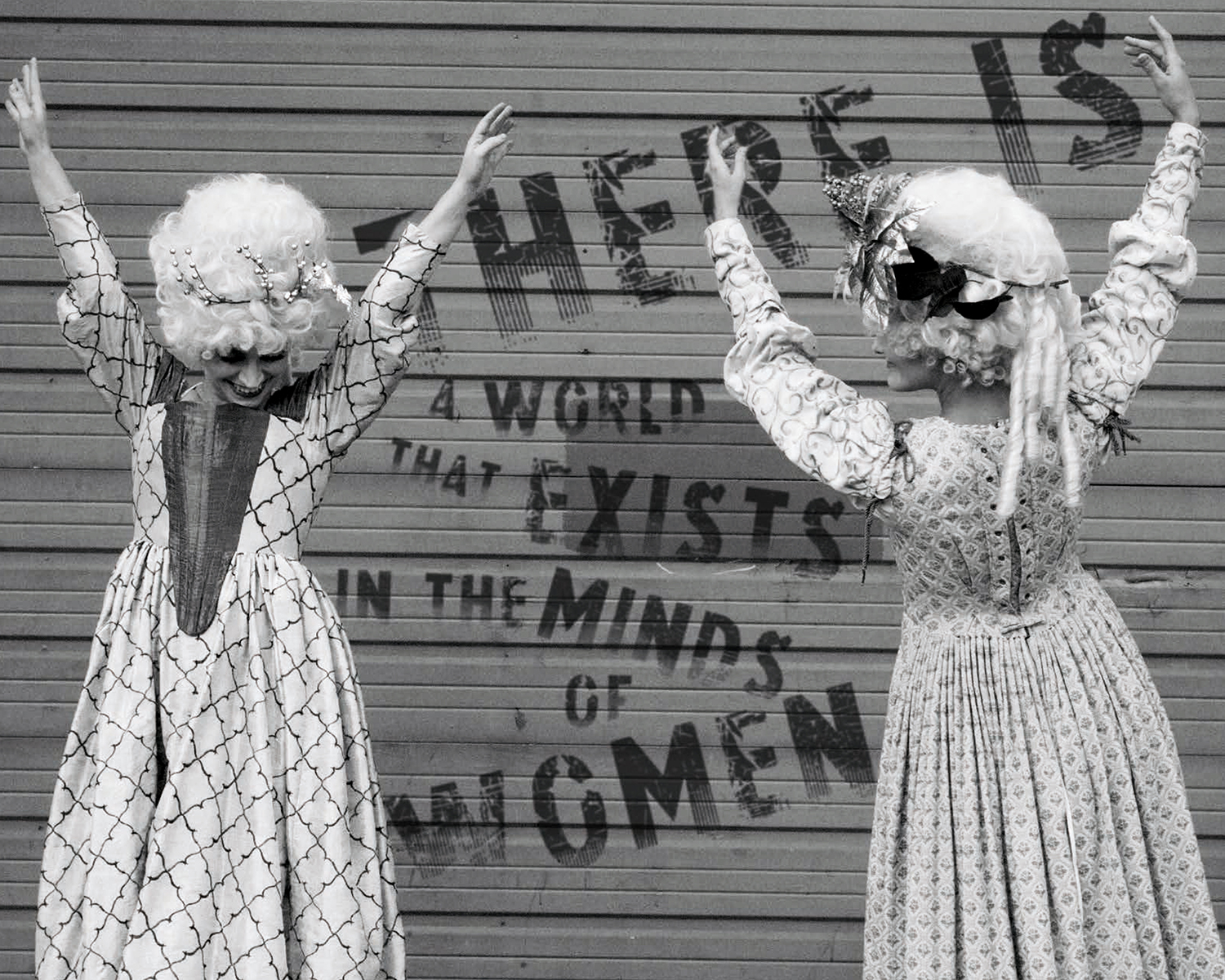

Morgan: Like Johnson was saying, there are all these opportunities to direct new plays and to ‘pitch’ yourself to playwrights as a director. I have been doing that, and I have relationships with playwrights that I like, but it’s really rare for an opportunity like this to come, for someone to ask me, the director, What do you want to do? So for the play, Johnson originally proposed it be a great American play, so I was thinking about Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, but I really wanted to fill that slot with a work by a female playwright. I love Caryl Churchill, and I’ve always loved her, and I feel like she’s not done enough in New York or America in general — she’s not as well known here, she’s in England. And she’s one of the greatest living playwrights. So it felt like a really special opportunity to do a Churchill play, whereas that would not happen in the city, and nobody would let me do it, unless I self-produced it. So I jumped at the opportunity, and Far Away is a play that I’ve wanted to direct since the first time I read it. I had visualized it when I was reading it, which is a good sign. I didn’t direct it when I first encountered it because I didn’t understand the ending. As I came back to it for this as an option for the middle slot, I still didn’t really understand the ending, but I was kind of excited by that challenge. I was also excited by its relevance, how it feels like the whole world is going to war, struggling with the responsibilities as an artist, and the distance between art and politics. Caryl’s is being self-aware and critical about artists, and I was excited to engage with that.

I was also really excited by the contrast between Minor Character which is Chekhov — but it’s also extra Chekhov, because we do 6 different translations on top of each other — with The Music Man, a musical with 27 people and huge, with this really spare, really poetic dynamite little play in the middle that is 45 minutes long, but has three distinct time periods and worlds within it, with this crazy hat parade spectacle. I got to have that theatrical event happening that is physical and design-based, which feels like an essential part of theater to me. I’m not that excited about plays that are just people talking to each other. It basically has all the things I like about theater in 45 minutes. [laughs]

Michelle: Well, that’s perfect then! You just mentioned being able to very quickly visualize Far Away. Is that how your process comes about most times? How do you negotiate between visual and literary cues?

Morgan: Yeah, I was thinking that [about Far Away because it can be seen] in terms of something that’s unusual. But to me it’s still not actually that radical because everything I’m doing this summer is text-based.

A lot of my work is text-based. The text is almost always the first thing versus a visual or an idea. So for me it does start with the text, and sitting alone and visualizing the text, and it feels right if I can get a picture [in my head]. It’s very instinctual, and it’s also about choosing the right material for the setting. I have maybe a bucket list of plays or projects that I want to do, but it doesn’t feel real till I’ve seen the space, see what would work in the space, what would be good for the audience at this time; it’s like this perfect storm of things that have to click into place.

Michelle: So how did the choice of The Music Man come about?

Johnson: I had two musicals in mind that I didn’t say anything about, but Morgan immediately said, I really want to doThe Music Man, and that was the show I wanted her to do. The story of a con man who comes to middle America is … so real.

Michelle: Absolutely. We just saw Death of a Salesman last night.

Johnson: Oh! Theater Mitu’s? What did you think?

Michelle: We loved it. We sat in the front row, so it was incredibly immersive. We very much interpreted it as empathizing with a Trump voting family. I also hadn’t seen that play in so long that I forgot about how agitated I get sitting through Willy’s monologues. It was very much like… dude, get a grip. We ran into a large group of friends and many of them didn’t make that connection, though.

Morgan: Oh, wow.

Johnson: That’s wild.

Michelle: They were either thinking about their own fathers, or family or friends, or whatever it was. Anyway, it just seems like it’s something that’s popping up everywhere, and folks are making connections whether the directors meant for it or not.

Johnson: Well, [Willy] is so emblematic of the worst parts of our culture. So as we look at these stories of patriarchy, and whiteness, and oppression, he’s in all of those.

Morgan: One of the things I was trying to deal with after Trump was elected — there was all this criticism about him, obviously, leading up to the election, every horrible thing he did, every lie, and everything that was revealed that was like, Is this the thing that’ll take him down? No, that’s not it. There was nothing that happened that was so bad that would prevent him from succeeding, so I was thinking about the public that elected him, and that there was more of those people in New York, around me, than I realized. So I was really connecting to The Music Man in that it’s a story about townspeople in middle America who accept a fantasy and enjoy it, because it sounds good and it feels good. They just buy into it, even when they find out that it’s a fantasy and they’ve been lied to and cheated. They kind of forgive this white guy. So I was interested in looking at myself and people who enjoy the feeling of believing in a fantasy. That’s so much a part of the American dream and the American psyche, and advertising, and Twitter — I mean, we’re just fed pieces of information and we consume them, digest them, and take them for truth. We don’t stop to think or criticize. And if we do, and something is revealed to be a lie, we’re still okay with it, because it felt better. It feels better, and is more satisfying to just buy the fantasy. And I experience that too in myself, so it was not so much getting to Trump voters specifically, but at American people who buy the fantasy.

Michelle: I definitely looked up the exit polls for this town when I was preparing for this interview. [laughs]

Morgan: You did?

Michelle: It went…

Johnson: For Hillary.

Michelle: Yeah, well, 800-something to 500-something. So it’s interesting to me. I also looked up the demographics, which says it’s about 98% white. This summer season you’ve put on and are putting on work that is perhaps challenging to the audience, but I wonder, at a place like the Sharon Playhouse, is there any fear of touching on subjects like racial disparity, gender disparity, or any marginalized issue, without basically pissing off most of your subscriber base?

Johnson: This pocket of Connecticut, Litchfield County, is in many ways a weekend community. So many of the people up here are city people, who come up here on the weekends. So it’s a sophisticated bunch.

Morgan: In Minor Character, men play women, and women play men, and actors of all races play the different characters. It’s really fluid, and one person who came to a dress rehearsal that the only good part of the show was when the women were kissing each other. So I feel like there is also that contingency of an audience here. There’s also people who totally loved it and embraced it. I think New Saloon, my company that I made Minor Character with, I don’t think we’re trying to make a bold statement about racial politics in our piece, but we are making a statement about identity and its fluidity and how we all hold many identities inside of us. I think that the intentionally diverse casting is trying to crack open some stereotypes. The diversity in the casting of that piece is essential to the project. We couldn’t do Minor Character with an all white cast. That felt important to get to do here.

Michelle: In that sense, what do you think of color conscious casting, which is what I’d call what you just described in Minor Character’s concept, versus a director and casting director trying to check off boxes in trying to satisfy diversity in a way?

Morgan: I try not to do those kinds of plays, or if I do, I play against it. In The Music Man, the Paroo family is written as an Irish family, which had more social stigma when it was first originally written, but no longer does. So I’ve cast the Paroo family as an African American family. The storyline is about how Marian is treated in this town in Iowa, so I think it heightened the urgency, especially because of the whole plotline about her younger brother and his safety and success in the world. So there’s a young Black boy running around in a town that is stirred up by this white guy and it becomes sort of an angry mob. That’s really scary right now.

Johnson: In the run-through today, I was so struck by the line about Winthrop’s father being killed, about being dead, which is usually, like, whatever. But when you have this young Black boy, upset, and his mother trying to explain things to him, it just made me think of Philando Castile, and so many others…. All the black bodies that are being killed every day, and those children that are left behind…

Michelle: Absolutely. I’m very interested in coming back and seeing it done in this way. I want to now zoom out a little and go back to a great point that was brought up, about the disparity between fellowships and mentorship for playwrights versus directors. I would argue there are even less for designers. Though all this seems very doable to me.

Johnson: Yeah.

Michelle: So, how has the experience been, what are the lessons learned, and what can others take away from this type of programming? How would you encourage other artistic directors or administrative folks to be inclusive in their guidance of emerging theater artists?

Johnson: It’s a leap of faith. You have to trust the artist. I’ve only seen Morgan do one show.

Morgan: He was very trusting. I couldn’t believe it.

Johnson: Well, I don’t think great work happens without great risk. There are so many theaters in this country. There are so many theaters in New York that are picking the trusted directors, the old steady hand, with the way that it has been done before. It feels to me, if I’m going to be a young artistic director, I should do something different. I should make a different choice. I should think about who’s going to make the next great theater, and give a platform. I’m really proud of Morgan’s work, and now she’s had three big productions in a row. I won’t speak for whatever she’s learned, but there have been insane learning moments. No artistic director can ever tell her she’s not ready to do a musical. No artistic director can tell her she doesn’t know how to do a stylized Caryl Churchill play, you know, and that’s so exciting to me. To give her that experience…

Morgan: Yeah, it’s a ton of experience right in a row. It forces this kind of feverish creativity.

Michelle: It must be all overwhelming.

Morgan: Very overwhelming. But it’s pushed me to be really collaborative with the designers and the actors and trust them in the way that Johnson’s trusting me. I think [Johnson] told me I brought about 80 people here, all in all.

Johnson: 70 people contracted.

Morgan: Right. So I brought my entire New York network with me. So it’s not like I actually did this by myself, you know? There’s a lot of other people involved. The pressure I find useful, but that’s just the kind of person I am. I like the pressure, but it is and was overwhelming.

Michelle: Right. Because other than the Lincoln Center Theater Lab—

Morgan: Right, which is not practicing, it’s a lab.

Michelle: Exactly. Other than that, I don’t think I’ve heard much else for directing.

Morgan: There are a lot of residencies and apprenticeships that are centered around assistant directing, and I’ve done a lot of those, and it’s a good way to learn, and met a lot of people I learned a lot from. In terms of getting our hands dirty, and making work, there’s not a lot of opportunity for that. There is in London, for example, so it feels like there’s a real dirth for directors in that.

Michelle: In Europe, to my knowledge, it’s mostly government subsidies that allow that to happen though, right? We are on a different system.

Morgan: Yes, it’s a completely different structure.

Johnson: Yes, but it used to exist in New York. New York Theatre Workshop, throughout the ‘80s, that’s where Michael Greif started, in the New Directors Project, where they would throw up these plays that were hugely foundational for a lot of the directors who are now directors on Broadway. The Public Theater, you look at what Joseph Papp was doing, he was finding young directors and just giving them rooms and giving them actors and paying those people, and saying, What happens in this room?

Michelle: That doesn’t quite happen anymore.

Johnson: It doesn’t quite happen anymore like that. I wish that all those Shakespeare plays in the park weren’t directed by Daniel Sullivan. I wish they were directed by young directors. We just keep seeing the same plays directed by the same people. It’s so boring.

Michelle: I agree. And so both of you are relatively young for being in the positions that you are in. What would you say is the steepest part of the learning curve so far?

Johnson: This summer has been a lot just in terms of getting 70 people up here to Sharon, Connecticut, and getting them all to the theater, making sure they’re housed. The logistics of producing here are tough. But in terms of the experience of being an artistic director…As a director, I’m always so nervous about sharing my own work, you know? And I have this sense of modesty, or I’m embarrassed to tell someone that I think what I’ve done is good. The great thing about being artistic director is that I get to scream from the rooftops about how special [Morgan] is, and that feels awesome.

Morgan: It also feels awesome to me. [laughs]

Johnson: But with the learning curve, I don’t know. Morgan and I haven’t agreed on every choice this summer. There have been some moments of disagreement. I think figuring out how to negotiate those disagreements has been a learning event.

Morgan: Right. And for me, it’d be how to take notes from an artistic director. I haven’t had that experience before, figuring out what things I can really negotiate on and what I need to fight for. Another thing that I think I’ve been getting better at out of necessity is articulating my ideas and my vision so that it is clear to people that are not inside my head, or don’t have the same relationship to theater as I do. To be clear about what I want to do, I have to change the way in which I’m describing it, based on who I’m talking to. I feel like being forced to do that so many times, with so many different kind of people this summer, I’ve gotten a lot better at it.

Michelle: Communication bootcamp!

Morgan: Seriously, yeah. I can’t assume somebody knows what something looks like in my head. I have to break it down.

Michelle: So as a theater and as directors, what do you hope the future of theater would look like? What do you want to see more of, or less of?

Morgan: I want to see more work that is breaking out of traditional theater conventions. I feel like I see a lot of theater that I’m sort of expecting. I feel excited to see work that is breaking the mold, so that in order for that to happen, people need to be given opportunities that aren’t necessarily given to them. So what Johnson’s doing here feels like that, but also for women, for queer artists, and people of color, having more opportunities to make their work — with support, because it’s so hard to do it on your own.

Johnson: I just want to see less of the straight white male gaze. I feel like so many of my theatrical experiences come through the viewpoint of a straight man, and we’ve seen that. I want to see so many more people’s work than I’ve gotten to see.

The funny thing is, in these Far Away talkbacks [which happens after every performance], there are people who love it, and people who are angry that the play makes them think. They’re angry because they’ve been challenged and not simply entertained It has emboldened me hearing that to only want to present work that challenges people, that challenges their perception of what should happen in a theatrical space. I want to make work and present work that people are still talking about later, that they’re still responding to. I’ve learned that so many people go to the theater and really want it to happen in there, and end in there, and to never engage with it again. I hope that nothing we do this summer ends in that space. I sort of hope that of all work.

The Wassaic Project, [an artist-in-residency program 20 minutes away in Upstate New York,] some of their residents came over, saw Minor Character, and loved it. They went back and told the rest of them, You have to come see this. They’re visual art people who don’t think that summer theater is going to be cool. They all came and lost their minds. I’ve now had so many conversations with people who have stopped working in theater because the rules of it, and the system of it, is so oppressive about the type of work that had to be made. So many of them have seen Minor Character and have been so inspired and thought, Oh right, theater can feel like this. It can feel dangerous and totally new while exploring something really old. I hope to keep being a part of work like that.

Michelle: Absolutely. Morgan, you mentioned quickly opportunity for women. I wonder if you can expand on your thoughts on opportunities for women and directors, perhaps particularly for musicals. I’ve been thinking a lot about not just what we touched on earlier about the lack of a support system, but even in terms of someone like me going to ‘diversity’ panels, and feeling like I’ve been going to the same one for five years in a row. It’s so circular. I wonder what a young 20-something just out of school can do beyond somewhat following the system that already exists.

Morgan: I can talk about my own experience with it, which is that I just made work. It was small, and dinky, and scrappy and self-produced, and I’d invite everybody I could to come see it. Most of them didn’t come until the third or fourth thing that I invited them to. I just kept going. A lot of the things I knew they wouldn’t come, but I’d invite them anyways, just so that by the sixth time – I guess I was pretty annoying… But it’s a dangerous line to walk because you can’t force yourself to receive recognition or gain support. It’s a delicate balance I think. But that’s what I’ve started to tell younger artists who ask me about it. Make work, and invite people to see it, as opposed to sitting and waiting. Instead of asking for opportunities, make them. I guess that’s pretty generic sounding.

Michelle: Yes, and it’s also hard to make it or make work as young theater artists if you don’t have some sort of financial support. So once again it becomes a very circular movement, where everyone who is able to make it in this industry is at least middle, upper-middle class.

Johnson: Totally.

Michelle: Yet theater is suppose to be a form of art empathy, and yet the spectrum of voices needed is impossible to achieve with this current model. It’s frustrating.

Morgan: That is really frustrating, and I think that without financial support, what I have noticed is that it just takes a lot longer. If you have that cushion, you can just do your work all the time and nothing else. If you’re working to support yourself, it’s a much slower slog. It takes a long time to get anywhere.

Johnson: That’s the worst. That sucks. It sucks that the big institutional theaters aren’t doing more.

Morgan: This is the first year that I am freelance directing and not doing five other jobs. So I tutored, did admin work, waited tables, did all the things. I actually have no idea if I’ll be able to sustain this. It’s very up in the air, so we’ll see.

Michelle: I think and hope that you will. Lastly, any other advice, and what’s next for both of you, after The Music Man?

Morgan: What I said before, I think: Make work. Sometimes you do have to be silent for a really long time and listen and learn. I was so frustrated by doing that for so long, but now I’m feeling grateful for putting in that time. Also, going to see stuff and learning from other people.

What’s next for me, is I’m directing a play by Milo Cramer, who is in New Saloon, called Cute Activist, at the Bushwick Starr in January. We just did a reading here this summer actually, very casually. Johnson read in it [laughs] and it was amazing.

Johnson: I would agree, make work, find artists you love and write to them and tell them you love their work and ask how you can help them make their work.

Morgan: That’s so good.

Johnson: Because the most important way to get people to come see your work is to be a part of a community. I think singlehandedly that is the key to success. It’s such a small world, and people want to help their friends.

Morgan: That’s true.

Johnson: And be nice to people. Don’t be a jerk.

I don’t know what happens next! This has sort of been a big, grand experiment. I think at the end of the summer we will take stock, and see what’s right for the playhouse moving forward. And I’m going to try to make some work. Morgan has very much inspired me to.

Michelle: Amazing. That’s the best type of collaboration.

Johnson: And I made a friend!

Morgan: Yes you did!

[Everybody laughs]

Johnson: It’s the best part of it all.

Michelle: Wonderful. Thank you so much for sitting down with me!

Morgan and Johnson: Thank you so much!

Morgan Green is a theater director and co-founder of New Saloon. She is thrilled to have the opportunity to direct three shows at the Sharon Playhouse this summer. Recent credits include Minor Character: Six Translations of Uncle Vanya at the Same Time (The Public Theater), I’m Miserable But Chance Scares Me by Milo Cramer (The Brick), Parabola by Sarah DeLappe (JACK), and William Shakspeare’s Mom by Milo Cramer (Ars Nova). Morgan is a New Georges Affiliated Artist, part of the 2012 Williamstown Theater Festival Directing Core, the 2013 Lincoln Center Director’s Lab, and a 2014-2015 Bob Moss Directing Resident at Playwrights Hoirzons. She was the Associate Director for Pam Mackinnon on Amelie, A New Musical on Broadway. Upcoming works include Cute Activist by Milo Cramer (The Bushwick Starr) and the West Coast Premier of The Wolves by Sarah DeLappe (Marin Theatre Company).

Johnson Henshaw is a film and theater maker. He has developed theatrical work with New Georges, New York Theater Workshop, PS122, Dixon Place, the Public, and the Goodman Theater in Chicago. While at the Public Theater he assisted the writers Tony Kushner, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins play An Octoroon whose production would be cited by the MacArthur Foundation when they awarded Mr. Jacobs-Jenkins one of their ‘Genius Grants’. For nearly 3 years Mr. Henshaw produced a monthly performance review in Brooklyn called Pillow Talk which featured performers such as Erin Markey, John Early, Kate Berlant, and Sasheer Zamata. Because of Pillow Talk, Johnson was approached by the Meredith Corporation to create and produce a comedy web-series for their new coporate channel DIGS as part of the Youtube 100 Channel Initiative. Johnson and co-creator Kim Rosen created Craft & Burn which the New York Times called, “raucous, and darkly funny.” In 2013 Johnson was selected by the Film Society of Lincoln Center to take part in their first Artist Academy, a laboratory for emerging filmmakers. He is a co-founder of Nobody Cares Productions with Kim Rosen. Their first television pilot “Entrepeneur” was bought last year and ultimately lost on the shelves of development. Johnson splits his time between Sharon and Greenwich Village with his partner Michael and their poodle, Henry.

Timothy Huang is a New York based writer of new musical theater. His full length musical Costs of Living was the recipient of the 2015 New American Musical Award, and the 2015 Richard Rodgers Award. Other works include Peter and the Wall (2013 Rhinebeck Retreat), And the Earth Moved, (CAP21) Death and Lucky (MacDowell Fellowship), the song cycle LINES (NYMF), A Relative Relationship (Winner, Best Musical, 2013 SoundBites Festival) and Missing Karma (2016 Samuel French OOB Short Play Festival). He is the creator of the one person musical The View From Here (cast album available wherever digital music is sold) and was a 2012 Dramatists Guild Fellow. He is also the recipient of the 2013 Jerry Harrington Award, a Fred Ebb Award Finalist and a two time Jonathan Larson Grant finalist. His song Everything I Do, You Do (with co-lyricist Sara Wordsworth) was recorded by Sutton Foster for the charity album Over the Moon: The Broadway Lullaby Project. To see a website made before the advent of smart phones, please visit

Timothy Huang is a New York based writer of new musical theater. His full length musical Costs of Living was the recipient of the 2015 New American Musical Award, and the 2015 Richard Rodgers Award. Other works include Peter and the Wall (2013 Rhinebeck Retreat), And the Earth Moved, (CAP21) Death and Lucky (MacDowell Fellowship), the song cycle LINES (NYMF), A Relative Relationship (Winner, Best Musical, 2013 SoundBites Festival) and Missing Karma (2016 Samuel French OOB Short Play Festival). He is the creator of the one person musical The View From Here (cast album available wherever digital music is sold) and was a 2012 Dramatists Guild Fellow. He is also the recipient of the 2013 Jerry Harrington Award, a Fred Ebb Award Finalist and a two time Jonathan Larson Grant finalist. His song Everything I Do, You Do (with co-lyricist Sara Wordsworth) was recorded by Sutton Foster for the charity album Over the Moon: The Broadway Lullaby Project. To see a website made before the advent of smart phones, please visit

ANN HARADA is best known for playing Christmas Eve in the Broadway and West End productions of AVENUE Q and stepsister Charlotte in RODGERS + HAMMERSTEIN’S CINDERELLA. Other Bway: Madame Thenardier in LES MISERABLES (revival), 9 TO 5, SEUSSICAL, and M. BUTTERFLY. She performed her solo concert in Lincoln Center’s American Songbook series in 2014. Film: SISTERS, TROUBLE, YOUTH IN OREGON, ADMISSION, HOPE SPRINGS, FEEL, HAPPINESS. TV includes: SMASH (recurring as Linda, the Stage Manager), LIPSTICK JUNGLE, 30 ROCK, DOUBT, THE GOOD WIFE, HOUSE OF CARDS, MASTER OF NONE, THE JIM GAFFIGAN SHOW (recurring as Stevie, Jim’s clueless agent).

ANN HARADA is best known for playing Christmas Eve in the Broadway and West End productions of AVENUE Q and stepsister Charlotte in RODGERS + HAMMERSTEIN’S CINDERELLA. Other Bway: Madame Thenardier in LES MISERABLES (revival), 9 TO 5, SEUSSICAL, and M. BUTTERFLY. She performed her solo concert in Lincoln Center’s American Songbook series in 2014. Film: SISTERS, TROUBLE, YOUTH IN OREGON, ADMISSION, HOPE SPRINGS, FEEL, HAPPINESS. TV includes: SMASH (recurring as Linda, the Stage Manager), LIPSTICK JUNGLE, 30 ROCK, DOUBT, THE GOOD WIFE, HOUSE OF CARDS, MASTER OF NONE, THE JIM GAFFIGAN SHOW (recurring as Stevie, Jim’s clueless agent).

Bear Bellinger is an actor, writer, singer, bartender, activist, and all-around trouble maker based in Chicago.

Bear Bellinger is an actor, writer, singer, bartender, activist, and all-around trouble maker based in Chicago.