Darrel Alejandro Holnes’ Bird of Pray (recently featured as part of the Brick Theater’s Festival of Lies) beautifully uses spoken word, language, and dance to illuminate issues of race, sexual identity, depression, PTSD, and the high suicide rate among U.S. veterans. We sat down with Darrel and choreographer Jonathan González to discuss their collaboration and creative process.

Margarita Javier: My pronouns are she and her. Could you introduce yourselves and say your pronouns?

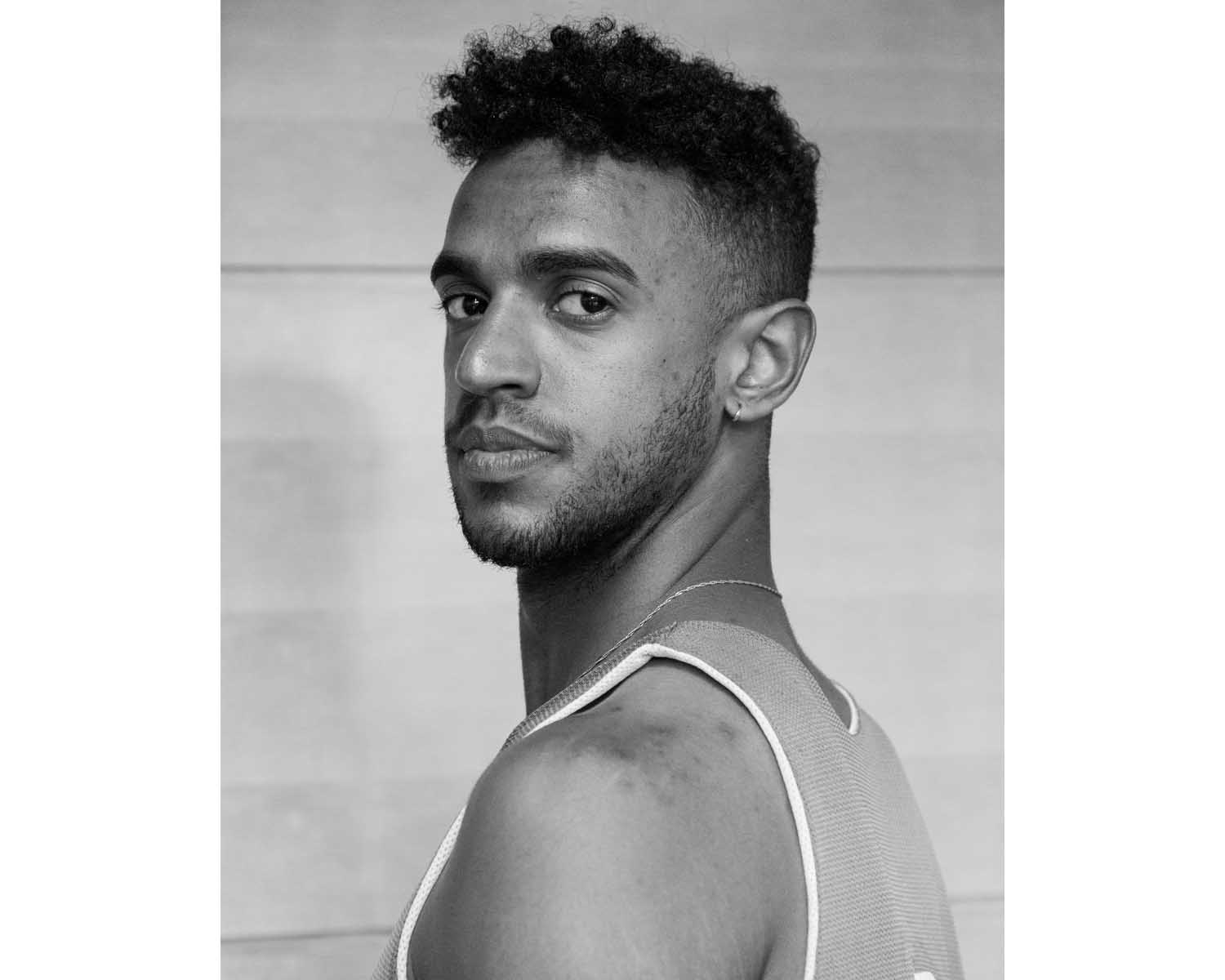

Jonathan González: My name is Jonathan González and my pronouns are he and him.

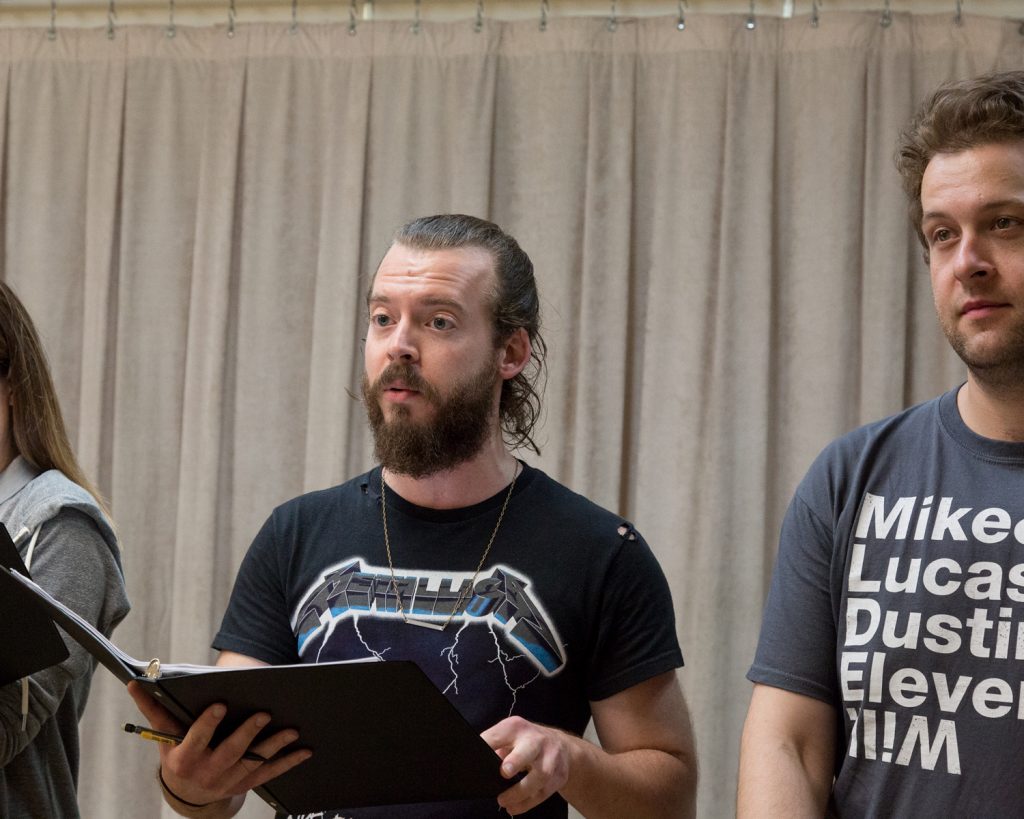

Darrel Alejandro Holnes: My name is Darrel Alejandro Holnes and my pronouns are he and him.

MJ: What can you tell us about the play, Bird of Pray?

DAH: Bird of Pray is about two characters who are African-American veterans and navigating the world of PTSD and mental health as one of them contemplates suicide, and the other appears with an interesting proposition: don’t kill yourself. Why don’t you share your body with me and together we can live a better life? So there are elements of magical realism in there, but it’s really based on several interviews that I’ve done with African-American veterans of the war in Afghanistan and the war in Iraq.

MJ: And what prompted your interest in having those interviews?

DAH: I was really inspired by conversations that I was having with veterans who are friends of mine, as well as folks that are connected to the military community through their family members. Growing up in Panama, I lived part of that life on military bases and have been a part of the military community because of that. I’ve kept in touch with a lot of those folks over the years and even contemplated enlisting myself. I think this is a part of that journey.

MJ: There’s a lot of dancing and movement in this play. How did you become involved, Jonathan?

JG: I think Darrel first contacted me about the work in its inception. What he was realizing after the residency appearance they had together was that he had an interest for movement — to see how movement could do what I think it’s now doing in the work. It doesn’t just supplement the text. It also provides an atmosphere and an arc of the body. It really speaks for itself in many ways without speaking a word. I think we spent that time trying to figure out what that could be.

MJ: What was that creative process like?

DH: I think of it as a symbiosis. We started with the text because I had already written out a description for how I imagined the dance to be, and then I shared that with our director, Mimi Barcomi, and he added shapes as to how my vision of the dance could fit his vision of the overall play. And then that was transferred over to Jonathan who came in and worked with the actors and modeled the dance, or made the dance on the actors who were really dancers.

JG: Josiah Vasquez plays the vulture in the work. He’s the one body that you see not speaking, moving throughout.

MJ: Yeah, he’s moving in the background throughout the entire piece. It’s really interesting how your eye goes from the action, to the dialogue, to a movement and creates this beautiful relationship between all of them.

JG: I think we had that discussion before about trying to choreograph the vultures and understanding that they kind of functioned as a Greek chorus. Behind this veil, they reveal certain things, or they post commentary on certain things that are happening between the two.

DH: I was really excited by some of the ideas that Jonathan brought to the table, including having the vultures parallel some of the movement that the actors were doing on stage, and some of the tension between them. And so, in that narrative movement, we dive deeper into the metaphorical language of the play: their metaphors and the words, their metaphors and the actors, their actions and movement. There’s also a metaphor in the dance.

MJ: You mentioned the director Mimi Barcomi. How did you get involved with him for this project?

DH: I met Mimi at the Lincoln Center Directors Lab last summer and he reached out to me after seeing a reading of Starry Night, one of my plays, at the National Black Theater. Mimi was really inspired by that. He said Let’s collaborate. Let’s get something on its feet. And I was like Well, I have this play from a couple years ago. And back then the play was called Trigger. I decided to dust off the second act in Trigger and share that with Mimi and see what he thought. He was really excited about it and that started the process of turning that second act into its own play. And I’m really grateful to The Collective New York for giving us a residency, and the Arch and Bruce Brand Foundation for a production grant that helped to finance that residency. It really helped to make the play what it is today.

MJ: The play deals with a lot heavy themes: mental illness, post traumatic stress disorder, suicide. How do you approach talking about these themes in a respectful way, in a way to shed light on these issues?

JG: I think I’m going back to what you were asking before. The way that the movement was brought into the work was that the script was presented to me with certain highlighted sections. There were a lot of buzzwords and was I willing to scaffold something? Because I don’t think the process at large was about setting anything. Nothing is actually set. There’s a lot of ideas about how to improvise around certain concepts and keywords. That brings us back to this question about PTSD and these threads in the work. What were the words inside of the texts that were activating movement and how can those become most apparent? So I offered kind of anchors of movement or ideas of inspiration for how the body can move, and kept it consistent with the character and the plot as it was developing. Where I think you might see a contrast is with Josiah, for which maybe there is a kind of essence of leaning into a modernist dance, or something that’s about form and falls between being about meaning. It’s a very formal sculptural movement. What’s happening between the actors is a deep inroads. It’s very coded — it’s coded in the colloquial. It’s like a real gesture, a real pedestrian act. It’s all about trying to speak to those threads when they present themselves. The sections that we deal with.

DH: And I think for me in terms of language, the play offers a series of monologues that are really closely based on the responses to questions that I asked these veterans during interviews. I have a lot of reverence for these soldiers and a lot of respect for their journeys. And so even though it is my rendering and the characters are ultimately composite characters, a lot of the stories are true. I think that’s how you navigate it, by really seeing this play as an opportunity for them to tell their own stories. I try to honor that and really make the play an opportunity for that by making sure that those stories are true.

MJ: You mentioned magical realism as being part of the story. Could you expand on that?

Where does the inspiration come from to use magical realism both in the text and dance?

DH: I don’t want to give too much away, but I will say that magical realism for me started with dance because I saw Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring at BAM. I saw Ligia Lewis’ Minor Matter in which Jonathan performed. I saw What the Day Owes to the Night by Herve Koubi and Compagnie Hervé KOUBI at the Joyce Theater. I was really fascinated by how narrative was one of the threads that tied the movement together in each of those pieces, and it got me thinking really creatively about how I could incorporate dance into this piece. I knew that it would be through magical realism because I would have to create a world where dance could naturally be part of the language of these characters, as someone who’s coming from Latin America and having a real appreciation for magical realism. That’s one of the reasons I’m also excited to collaborate with Jonathan because of his connection to Latin America as well. I’m really thrilled that we found a way to collaborate together to make this world a real one onstage.

JG: In dance, there’s definitely a kind of intense hybridizing, especially when you’re talking about people who are coming from the black diaspora, from the African diaspora. They really have been thinking critically about magical realism as being a way of being resilient and so dance has been doing that and I’m very inspired by those people who do that. So they’re in the room.

DH: I would also say that in terms of magical realism, there are dances in the piece that are part of African-American ritual or west-African ritual, or diaspora ritual. And in that way, we’re really honoring culture and honoring the ancestors. I do think that that makes room for there to be an element of magic in the play because it is a kind of lifting of the veil or an opening of a door of sorts in a respectful and reverent manner. And I was so happy. One of my favorite memories so far is when, in the early parts of our collaboration, Jonathan was teaching the Ring Shout and the Rain Dance to Cornelius Davidson who plays Shaq and has to take on the majority of the dance, at least in the first half of the play. That really felt like a moment that put me in touch with the ancestors, just by watching this happen. And it was an opportunity for us all to learn what those steps were about. Jonathan said, and you’re right here, so why should I paraphrase it? Can you talk a little bit about what a Ring Shout is in the Rain Dance?

JG: The historical reference of a Ring Shout is coming from the African slave trade as it resides in the Commonwealth of the United States. And the practice of stomping the feet, the circle, and the group dance is something that we can tie it back through the diaspora as a kind of ritual practice, but also as an art practice, and the stomping as a gesture, as a way to deal with the dead. It’s like the pounding of the soil, the awakening of what has passed or the coming together of what is alive. It’s like an allegiance of life and death. And so in the Ring Shout and also the Rain Dance, which is also in the work, we’re thinking about the old traditions and the practices of Yamayá. Those are also located in santería and many others as we talk about the lineage of coming from Europa. But how these operate in the work because it is within a storm, right? We hear the track of the storm, we hear this situation of a kind of conjuring, and we think about weather patterns and also the spiritual and also blackness wrapped into each other. It’s very historic site.

DH: When I interviewed a lot of these veterans, some of them expressed that they were searching for something to make sense of their experiences. Searching in a way that led them to spirituality, sometimes towards religion, sometimes away from religion, into an abyss or a void of unknowing. But always still searching and with these characters, I think what they’re finding is themselves and a kind of beauty, if you will, in the tragedies of war through the rituals that they’re working with on stage. So I’m really excited about being able to incorporate that in the play with Jonathan´s support and direction. And I’ve really been happy with how the actors have been able to successfully bring all of those elements to life as well.

MJ: At the heart of the play is this love story between two men who were both soldiers and they’re both black and it’s really beautiful to make that connection between culture and history and queerness. Can you speak a little about the history of gay soldiers in the military, or if soldiers of color in the military, and how those stories aren’t as well known and have been sort of in the shadows for a long time?

DH: Well, one of the reasons why I really am drawn to this community is because so many of the stories related to LGBT service in the military specifically focuses on gay, CIS, white men. And so many stories of veterans in general focus on straight, CIS, white men. With all of my work, I always think about who is left out of the history books and I take it on as a mission to write those stories into the history books by writing them into the history of the American stage. And so this is really made to honor those stories which are complex and full of contradiction and sometimes the stories are completely opposite experiences because we are diverse people, right? Some people have it great, some people have it bad, some people have up and down, some people have everything in the middle. And so I think it’s really important to show that diversity even within this specific community; to show the wide range of experiences within the military, within blackness, and within queerness as well.

MJ: The current president and the administration are openly hostile to the LGBTQ community, to the black community, to immigrants. Do you as artists feel any responsibility in taking part in the political discourse?

JG: I think no matter what work you’re making, it’s always political. I know that some people don’t want to agree with that, but I’ve been making work before this administration and it’s always been garnered on the idea of black life and the possibility of working with people that are trying to really work against them inside of the institution. So nothing’s changed.

DH: I feel that my work is in a lot of ways about memory and awareness. So you could argue that that in and of itself is a political act just by sharing these stories and telling these truths. Right? I hope that my work transcends politics because it’s not about Democrat or Republican. You know, LGBT folks had been mistreated in the military regardless of who’s president. African Americans have been mistreated regardless of who’s president. Latinos have been mistreated regardless of who’s president. I hope that this transcends politics and really touches the audience where it comes to how human beings treat each other overall. Because in every community there is, an outsider, right? There’s someone who we don’t let in; someone who we’re afraid of. And it’s usually because we don’t know their story. These plays tell those stories, so I do hope that whoever sees it, when they’re out there voting or when they’re out there deciding what to support, that they remember that these soldiers are people too.

MJ: And this play is part of a trilogy?

DH: This play is part of a cycle. There are currently three but there could be more. The plays are all part of what I call The Sandstorm Cycle. Sandstorm is a line that’s in one of the other plays, Nativity because all of those service men, women and people that I’ve interviewed have served in Afghanistan. Many of them have also served in other countries and in other conflicts, but they all have that in common. And so a lot of the stories take place in the desert. A lot of those stories take place in that landscape. I think as someone who is either a millennial or on the cusp of being a millennial, I think that our experience of U.S. wars has everything to do with the Middle East and so a lot of the stories come from soldiers with those experiences specifically. All of the plays are based on interviews that I’ve done with African-American veterans, but recently it started to expand and I’ve been including other LGBT veterans, as well. I’m really excited to share these stories and to bring them to the stage. And I’m also really grateful for how they’ve been received so far. Nativity was selected for the 50PP list, and Starry Night was a finalist for the O’Neill National Playwrights Conference and Trigger, which is related to Bird of Pray, was a finalist for the Princess Grace Award. That’s helped the play; it’s gotten a lot of interest and attention from other theaters, and even possibly landed this great opportunity [at the Brick Theater]. So I’m really grateful for the theater community for being receptive to these stories and I hope that we can all continue to collaborate together bringing them to life.

MJ: You almost already answered my next question: what are your hopes for the next steps of your work?

DH: I hope to continue to collect more stories and to bring them to life on the stage and to continue to collaborate with great artists. I really hope to continue to also explore the ways that theater and dance can come together. Recently, I was in Europe doing a little short tour hopping around theater and performing arts festivals and was really inspired by how the lines between the performing arts are really blurry and some would say perhaps even don’t exist, or are only the limits of your own mind. And so here’s to hoping that more of the contemporary American theater can be like that and that collaborations like this can continue to happen. It’s really an honor to collaborate with an all queer team. And it’s also really exciting to share this play with Brooklyn during PTSD Awareness Month, during Pride and also at a time when suicide prevention is part of the national conversation because it does figure significantly in the play. I think it’s a really important conversation to have. On average, 20 veterans a day commit suicide, which is one veteran every 65 minutes. Suicide is within the top 10 causes of death in the United States. And in 2012, suicide was the number one killer among veterans or amongst soldiers from the United States. And that was the first year that it climbed higher than actual combat. This is an epidemic and with trends of suicide within the LGBT community, as well. You can imagine that even though a lot of studies are still being done right now to look at that cross section, that there’s a lot of overlap between the trends of suicide within the LGBT community and trends of suicide within the veterans community. And so that’s one of the reasons why I think telling these stories is so important because it really does affect a significant amount of people.

MJ: This is a somewhat a loaded question, but what can you say about the fact that the United States, one of if not the most powerful country in the world, in large part because of its military, treats its soldiers so poorly? As you said, the suicide rate is so high amongst veterans, and so many of them live in poverty and their spouses don’t receive support.

JG: That’s Neo liberalism, isn’t it? You make bodies utilities, and that’s what this country is good at. But I think the disillusionment is when we all think as Americans that it hasn’t been happening and what we packaged and digested over the process of believing in the nation state of America, is that we haven’t had our hand in everything international and haven’t been using bodies in a disposable way. We’ve been doing it here for black people for centuries. So it shouldn’t be different that those who fight in the name of this country die forgotten.

DH: I would add that I hope that anyone reading this feels encouraged to support the vets and are encouraged to promote mental health literature and services in their community, because they call it performative empathy and it actually does make a difference when someone is considering suicide. Just having the opportunity to talk to someone about it really does help people feel heard and seen and could turn the tides. I would really encourage folks to do that. And I think also, it’s really important that we as a nation and we as human beings in this world try to solve our problems in ways that don’t involve war, right? So that we can reduce the amount of human casualties. I think everyone who cares about their family, their community, their nation, or just humanity in general should always be looking towards other means like diplomacy and just good old fashion sit down conversation as a first resort rather than as a last resort. So I really hope that that happens.

I would just add that there’s a lot that we still don’t understand about PTSD. So I think supporting research is going to be vital and I also think that there are a lot of good folks at the VA who are doing everything they can to work with these soldiers and they need support as well. There are a lot of things that doctors, nurses, and researchers ask for and are struggling to get. I hope that Congress and everyone in power can give these folks the supports that they need so that they can continue to provide – and hopefully provide better – services for our veterans because they certainly deserve it.

MJ: Can you name a few organizations to help support veterans?

DH: Here are some ways folks can support our veterans: Wounded Warrior Project, Semper Fi Fund, and Fisher House.

Jonathan González ambulates between the roles of performer, educator, and choreographer – initiating questions through the body alongside composing sound, design, and text for performance. His works have been presented among others by BAX/Helix Queer Performance Network, New York Live Arts, Center for Performance Research, La MaMa, and Danspace Project. A CUNY faculty member, artist-organizer with WoW/Works On Water, previous curator for Knockdown Center’s Sunday Service, and co-curator for Movement Research’s Fall Festival invisible material. Diebold Awardee for Distinction in Choreography & Performance; POSSE Scholar (Trinity College); Bessie Schonberg Scholar (Sarah Lawrence College/MFA). Jonathan is based in their hometown of Queens, NY.

Darrel Alejandro Holnes is a poet, playwright, and director from Panamá City, Panamá, and the former Panamá Canal Zone. He is a member of the Lincoln Center Directors Lab, the Musical Theatre Factory’s POC Roundtable, the Stillwater Writers Workshop, and Page 73’s Interstate 73 Writers’ Group. His play BIRD OF PRAY was a recent finalist for the Princess Grace Award, and his play STARRY NIGHT was a recent finalist for the 2018 O’Neill National Playwrights Conference, the Van Lier Fellowship from The Lark Play Development Center, and the 2050 Fellowship in Playwriting at NYTW. His other plays have been developed with the generous support of the Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts, the Virginia Center for Creative Arts, the Kitchen Theater Company, National Black Theater, the Arch and Bruce Brown Foundation, and the Collective NY. He is currently an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing and Playwriting at Medgar Evers College and he teaches playwriting at New York University. darrelholnes.com

Rachel Griffin is a 2015-2016 Dramatists Guild Fellow whose compositions have been showcased at 54 Below, 47th St Theatre, the Musical Theatre Factory, Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, the New Light Theatre Project, Rockwood Music Hall, The Living Room, and Hotel Cafe. She has won two National songwriting contests, the NPR Historic Songwriting Contest and the American Idol Underground Songwriting Contest. Griffin’s work has been featured in The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, The Mighty, PBS News Hour chats, Art With Impact and on CBS News. She has created several viral videos, blogs, and the viral Twitter campaign #imnotashamed. She is writing full length musical about mental health that can be found at

Rachel Griffin is a 2015-2016 Dramatists Guild Fellow whose compositions have been showcased at 54 Below, 47th St Theatre, the Musical Theatre Factory, Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, the New Light Theatre Project, Rockwood Music Hall, The Living Room, and Hotel Cafe. She has won two National songwriting contests, the NPR Historic Songwriting Contest and the American Idol Underground Songwriting Contest. Griffin’s work has been featured in The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, The Mighty, PBS News Hour chats, Art With Impact and on CBS News. She has created several viral videos, blogs, and the viral Twitter campaign #imnotashamed. She is writing full length musical about mental health that can be found at