As of 2012, the US Census Bureau estimates that close to 1 in 5 Americans have some form of disability. You’d think something that affects 20% of the population would take center stage a little more often, but theater has been slow to to present productions that truly represents people with disabilities and often when they do, able-bodied people are chosen to play roles that could easily be filled by actors with actual lived experience as a person with a disability. But for 37 years, Theatre Breaking Through Barriers has been creating art Off-Broadway with a mission exclusively focused on producing work for both writers and actors with disabilities. We sat down with Nicholas Viselli, the Artistic Director, to talk about the history of TBTB, the importance of inclusive casting, and the work we all have to do to normalize the experience and the art of actors with disabilities.

Michelle Tse: Where do you think your empathy comes from, as a Straight White Able-Bodied Man running a theater company that ‘breaks through barriers’?

Nicholas Viselli: In order to have that empathy, you have to filter through the intellectual stuff and identify with people on a deeper level. I have a sister with lupus, and both her and my older brother had epilepsy. I also lived with my grandmother, who had just suffered a stroke and couldn’t walk without a walker. I had a neighbor who spent time at our house all the time who had Down Syndrome. I have a cousin with cerebral palsy. My wife has multiple sclerosis, and she is a wheelchair user. I was immersed with a lot of different disabilities throughout my early life. Disability and diversity were never a big deal for me, and I was always attracted to people who were different from me because I found those interactions interesting. I can credit my parents with that, because in the town I grew up with, people were small-minded and if you were different you were segregated because of your differences.

Empathy is a combination of things. Another part of it is that you always have to be open and not shut the door and label. When you do that, you’re shutting out empathy and not acknowledging it. You need to keep feeding it and opening it up, because that will help you.

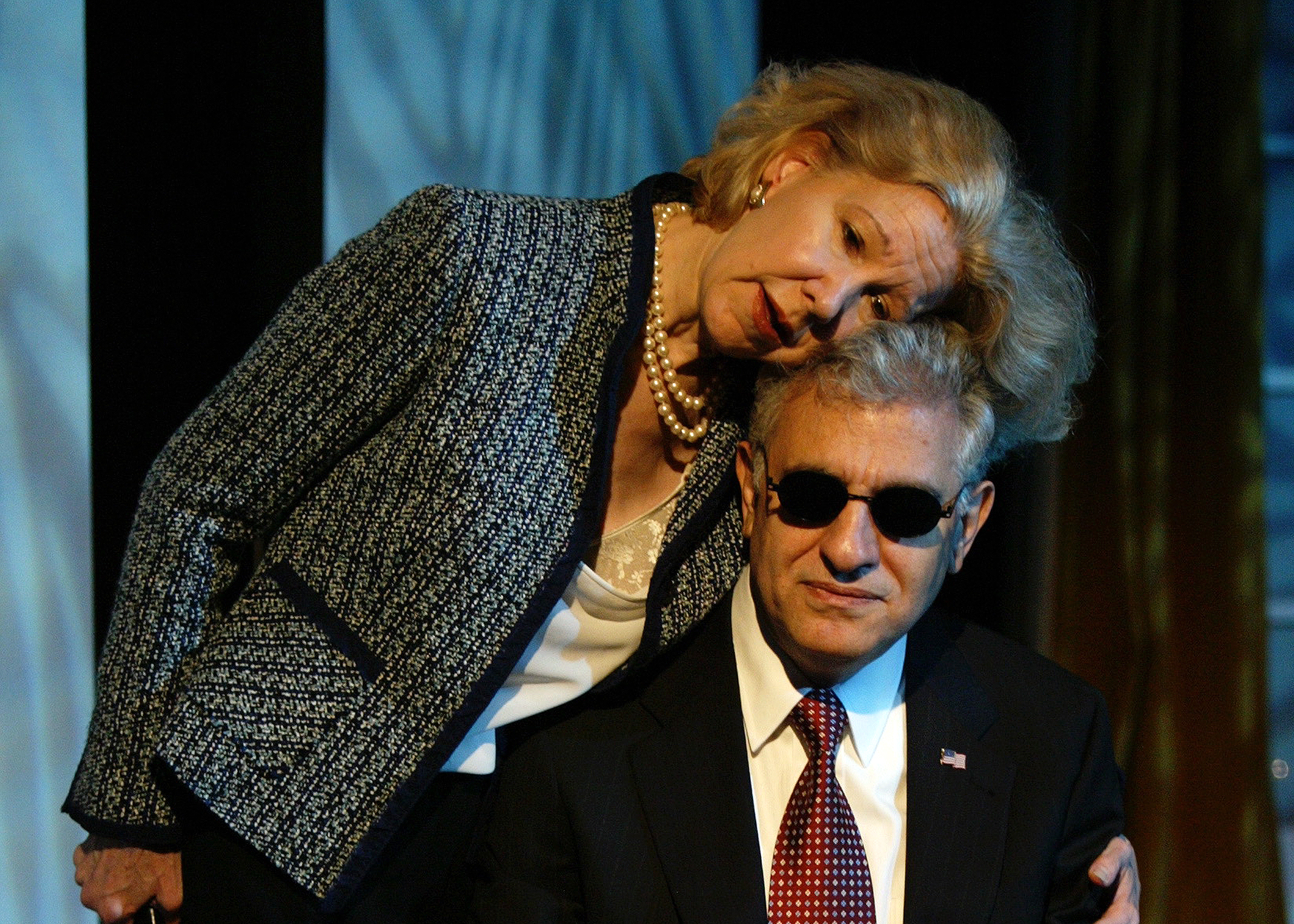

Helen Schultz: Can you talk a bit about how you became involved with Theater Breaking Through Barriers? I know you’re an actor as well as an artistic director.

NV: Richard Harris’s brother was producing the Camelot tour in the late 80s and it had stopped in my hometown. His brother passed away while they were on the road, so our local university, University of Scranton, said they wanted to set up a memorial scholarship in his name. Richard Harris was so moved by that that he said, “I’ve always had this idea to do a production of Julius Caesar and I want to take it to Broadway. I would like to do it in Scranton as a work in progress.” So I ran home when I graduated from Hofstra University and auditioned for the play and I got a small part.

There was an actor, George, in that play who managed to come in from New York and he was blind. He was wonderful and we became very fast friends, and he told me he worked with this theater company in New York called Theater By The Blind and they were doing a production of an Agatha Christie play called The Unexpected Guest. That was my first experience with TBTB. At that time, the artistic director was working with a lot of blind actors and creating performances in which you would not be able to tell whether the actors were blind or not. George was completely blind, and he was moving around the stage and it was a non-issue. At that point I didn’t think TBTB was an integrated company [the way it is now]. It wasn’t until about 10 years later that they started hiring sighted actors to do play readings, rather than printing scripts in braille and large print. One of those readings was how I started working with the company, and it was also sort of my audition. If the artistic director liked those sighted actors, he would continue to hire them and eventually feed them into the shows. So I really started working with the company in the summer of ‘97 and the company started growing and became a really solid professional corps.

MT: What have you learned, being the Artistic Director of TBTB?

NV: One of my biggest revelations through all of this as a new Artistic Director is that I want to be as open as possible. I don’t want to be limited. When you start building walls and creating parameters – in art, it’s all valid. If you only want to do plays that deal with being an Asian female, that’s great and it’s absolutely valid. If you are a theater company that only wants to do Jacobian drama, that’s great. And it’s great that we live in a city where you can do something that specialized and still thrive. But for my money, I don’t want to be limited by anything. I don’t want to just talk about disability because there’s more to life than that.

MT: It’s right in your company name, “barriers.” Breaking through barriers. Ah, those pesky walls.

NV: We’ve gotten criticized by saying, “oh you’re a company of disabled artists and it’s so great that you’ve got these disabled people breaking the barriers, aww, that’s so nice.” But they’re not getting it. It’s barriers of perception. We’re all others. We all have our limitations. We’re never going to be omniscient. The great thing about this life is that every person you meet is a new story, unless they’re putting up walls and identifying as something. Then they become less interesting. I want to know about you, not your label. That’s why I love theater and art, because it is the expression of humanity. We’ve become very compartmentalized and dehumanized. We spend so much time on our phones and in our own little worlds, and it’s much more interesting to live in your heart. Your head will mess with you all the time – it’s our greatest gift as humans and our worst enemy.

MT: To go back a little bit, how do you deal with triggers, offensive words, and labels?

NV: When you go through something without fear and limitations, you make the best art. We did Unexpected Guest last year and some advocates in the disabled community were very upset with us because the play was written in 1956 and there was a character in the play who has a mental disability and becomes one of the suspects in the murder mystery. In 1956, if you had a mental disability, you were called ‘retarded,’ and that’s the standard vernacular of the time. I wasn’t willing to change that because we were doing a play set in 1956. A lot of advocates were upset with us and said, you should at least have program notes that talk about it. I’m not going to change it because that turns into something else called censorship, which to me is more offensive than any other political correctness.

I had a discussion with David Henry Hwang, who has also written for us, about when he did Kung Fu, the play about Bruce Lee. In the 60s and 70s, if you were Asian, you were often called ‘Oriental.’

MT: I was actually called that just a few days ago.

NV: And you will be called that because there are older generations that grew up on that. Oriental, colored, crippled…

MT: They’re just not going to catch up. And us ‘others’ have learned to try to ignore microaggressions.

NV: I think the best way to do that is to talk to each individual and ask, how do you want me to address that if it ever comes up? I have a friend with cerebral palsy who says, “Yeah, call me a crip, I’m crippled, I don’t care.” If that’s how he identifies, I’m going to respect that. That goes for anything. Any type of vernacular. If a person identifies as that, I only care what that person thinks.

MT: It’s similar to people that are taking back the word “bitch.”

NV: David Henry Hwang said, “Of course I’m going to use that in my play because the play is set in that time period and in the 60s in San Francisco, people who were Asian were not referred to as Asian.” They were referred to as their ethnicity or as oriental as a general blanket term. And I agree with that. And as an artist, I want to be able to say and do whatever is right for the play. And if people are offended by it, good.

MT: It starts a conversation.

HS: How do you make sure that your work, or any work like this, is evaluated at the same artistic standard and treated as a serious piece of theatre?

NV: We had to fight that for a long time in our company. When we used to be Theater By The Blind, we had a great group of talented people – some experienced actors mixed in with some other people who were not as experienced – and it became a kind of community theater. The common theme was blindness, so it became a connection – so the work was not as professional. We were getting reviewed in the early and the mid-90s when we were still forming, and critics would come and say, “This is actually really good work for a group of blind artists.” And it’s like, don’t give me the “Special” award. If you’re going to judge the work, judge it at face value and judge it for what it is. And if it sucks, say it sucks! As a group of artists, that is what we need to hear.

HS: We also go so far out of our way to praise actors without disabilities that play people with disabilities, or actors who are not trans that play trans characters, yet we don’t privilege the stories of people who actually live that. Why do you think that happens?

NV: There’s this whole idea of what an actor must do to prepare and endure to create a role, the hardships they have to put themselves through and the positions they have to twist themselves into. Oh, I played someone who was blind, and for six weeks I lived in total darkness. It’s like, Great, that’s lovely and interesting, but why don’t you even consider hiring someone who has that disability to play that role?

MT: People seem to be afraid of what they don’t know or see every day.

NV: In theater and in film, they’ll hire a disabled actor to serve as an advisor. And yet they also say, “We don’t want to work with a blind person because there’ll be too much liability, too many demands, too much work. They’re going to have needs we won’t be able to meet.” There’s the star factor too. If I’m going to do a production of My Left Foot, I’m going to want Daniel Day Lewis. I don’t want someone who has cerebral palsy who I don’t know to play the role because I want to see Daniel Day Lewis do it. And then I can say, Wow he is really an amazing actor, because look at his range.

HS: It’s remarkable that the first person with an actual disability to play Laura in The Glass Menagerie is going to happen next season on Broadway.

NV: The fact that a major producer like Scott Rudin is considering and casting a person with a natural disability to play the role of Laura in Glass Menagerie is great and it shows that there is indeed progress being made.

MT: Disability is so often an afterthought in the conversation of inclusion.

NV: People always look at disability as something that makes a person less-than. You say, I have a disability, and they go “Aw, can I help you? You need a hand?” Because suddenly you’re a poor damaged bird who needs help. When it comes to disability, there are definitely people who are in a position where they might need more help than others, but it’s up to the individual to make those decisions. It’s not up to the society to make those decisions for them. That’s horribly condescending and it’s just wrong. It’s a perception that has been hardwired into us forever.

HS: And it’s so interesting that, as you said, it intersects with other forms of diversity. And yet, those categories usually become the more dominant form of diversity.

NV: The idea of non-traditional casting always came down to making sure that we’re being inclusive. If possible, we also try not to look at gender. I’ve always tried to address [issues of inclusion]. Our world is full of limitations; there are obstacles everywhere. If you have a disability, getting through daily life means you have to learn to really navigate through many obstacles. I don’t think anybody wants to be disabled, but if you become disabled or have a disability and you learn to adapt and live with it, you may realize, I don’t need my eyes, I don’t need my legs, I’m still me and that’s wonderful. The idea is that, if you were to become disabled tomorrow it would be horrible but you would learn to adapt and you would still want to be treated as you. And that’s how it is for everybody.

MT: So you’re talking about inclusion beyond disability at TBTB?

NV: I want our company to be able to explore all types of diversity. Most of the performers I know with disabilities are white. I don’t know a whole lot of actors with disabilities who are actors of color. I know they’re out there, and I want to work with them, I really want to meet them. Anytime you bring someone into a work, their energy and their life experience changes it and adds a different tone and color to it. It always makes the work richer. To me, that’s what’s exciting. Let’s see what we can get out of this.

MT: How often do you communicate with casting directors about inclusive casting?

NV: We’ve had a lot of conversations with casting directors, and they for the most part are on board. They want a fresh perspective and face. A lot of the issues with casting comes down to the money people, because they wonder, Is this person marketable or sellable? If they’re disabled, will people be uncomfortable with that? And that’s the perception we have to get over.

MT: I’m sure you hear a lot of stories from your cast members…

NV: We’ve had actors who have been told over and over again that they didn’t get a part because their disability was too real. You’re a congenital amputee, and that makes people squeamish. One of our actors, Mary, was up for a role a couple years ago in Army Wives. The part was for a female soldier who just came back from Afghanistan and she had lost her arm. Mary is a congenital amputee and is missing her arm. They auditioned her, called her back 6 times, and her agent thought she had it in the bag.

She didn’t get it, and the other actress who was not disabled got it, and they CGI’ed her arm out. They thought the cast and crew would be too uncomfortable being in the presence of an actor with a missing arm, that was why they did it. And everyone has those stories.

HS: Let’s talk about The Healing, your last production. It was written by Sam Hunter, and was commissioned for TBTB. Without giving it away, I found it fascinating that Joan, the one character in the show without a disability, is actually the most fragile and the one we’re most worried about. The rest of them have their lives so together. Sharon, for example, is this very successful woman. Her detriment is almost that she is so together.

NV: It’s very subtle but the fact of the matter is it’s about a group of people that are haunted by their past. Sharon especially, she’s haunted by Zoe – was I able to help her? Was I able to do anything for her? And all of them are haunted by the ghost of Joan, a second ghost in the play. She’s painted as this horrible person, she’s awful, so you expect this crazy fanatical woman to enter, but instead you get this very sweet fragile woman who is terrified. Which sort of says something about all of us. That’s something that says, when it comes right down to it, we’re all the same in that regard. We all can relate to this play because we’ve all had things happen to us in the past that have affected us, good and bad, and changed our lives. That’s the parameter of what this life is I think. But I think it is important to realize that the other great message is to realize that we all matter, we all leave something behind. You are influence over the people you interact with in your life. Maybe it’s not a huge influence at first, maybe we won’t feel that influence for months and years down the road, but it’s important to think that everybody you encounter sort of nudges you in a different direction or different way.

MT: So Helen saw the show when there was a primarily deaf and hard of hearing audience. I went when VISIONS was there. Do you partner with them? Do they come to most of the productions? How does your accessibility program work?

NV: They don’t always come. We try to do at least one open caption performance whenever we do a show, but it’s my goal to make everything we do fully accessible to everyone always. We’re not there yet and I’m not saying we’re gonna be there next year or even in five years. But it’s something we’re constantly working on. Until the time that we can create work that is fully accessible to all people at all times, there will be those limitations. This year we did two open captioned performances and we did not do an audio description performance, because I don’t think this show really needed an audio description performance. It was a very dialogue driven play, there wasn’t a lot of non-verbal action that a blind or low-vision audience member would miss. We did create a series of program notes for our braille programs so that if you were blind, if there was something that was a non-verbal indication, there would be a note about what that thing was.

MT: What about the time changes and flashbacks within the show?

NV: Our blind and low vision audience got that. They might not have gotten it right away, but if you saw it, you might not get it right away either. The lights change, but you realize eventually that Zoe was dead and now Zoe is onstage talking. We like to do talkbacks for all of our show, and we very intentionally did talkbacks for our Deaf and HoH audience and our Blind and Low Vision audiences because I really wanted to get their feedback. I wanted to know what they thought – did they miss anything? Was there something we didn’t do right? What could we have done better? I thought it was great that you guys attended those talkbacks.

MT: And John McGinty was in the show. I know from the talkback that the role was slightly edited to fit him.

NV: This was the first show that we worked with an actor who was deaf. We’ve worked with hard of hearing actors and actors with assisted devices, but John is deaf and needs an interpreter in the room. That was all a new but great experience. It’s work we should be doing.

MT: It’s often people that are empathetic and compassionate that actively look for shows that are not about themselves or the majority. We at Stage & Candor look at it and talk about it because we’re interested in confronting it. But the people who actually need to be there will never seek it out. Do you ever think about that with TBTB, about how you can somehow reach out to a larger audience and unexpected groups of people?

NV: The thing you have to do is just keep reaching out. If you try to force a message on people they will not want to hear it, especially when it comes to entertainment. People go to the theater because they want to be entertained, not because they want to be educated or talked down to.

It’s always been a tough thing for our company because, bottom line, disability doesn’t sell. People hear disability and they automatically think it is going to be less-than. I cannot tell you how many times we’ve had people send us a donation and say, “That’s great work you’re doing,” and I think, “Wait a second, how do you know it’s great work if you’ve never seen it?”

Our ultimate goal has always been to create great work. We want to do work that you’re going to want to come and see, and you will see a group of great artists, many of whom have disabilities, and it’s going to be an eye opening experience.

MT: Have you ever chosen to not disclose the fact that most of the company members have disabilities?

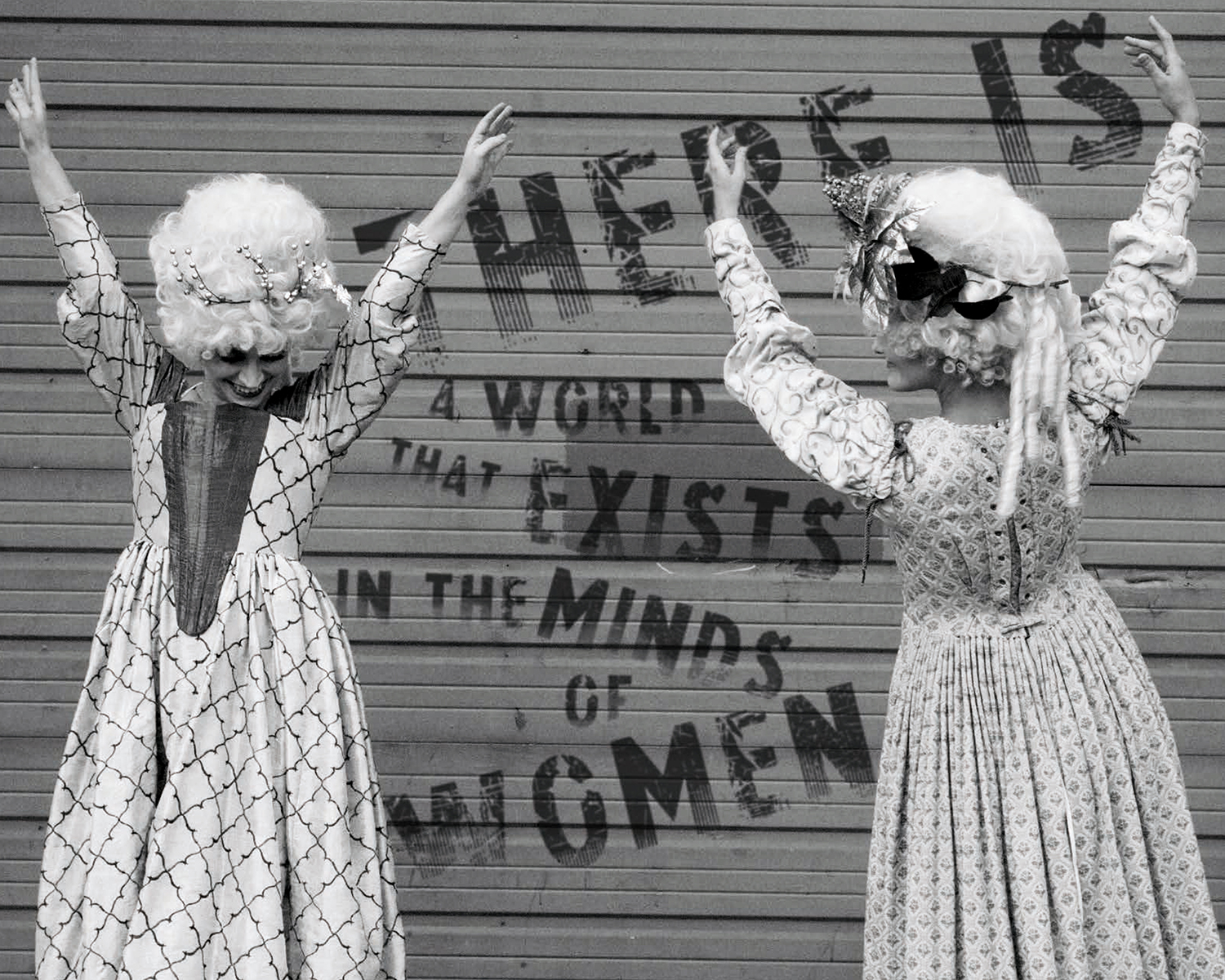

NV: As a non-profit theater, when we’re asking for funding, we want it to advance the work of performers, writers, directors with disabilities. Last year we did Agatha Christie’s The Unexpected Guest and sold out 95% of the run when we announced we were doing Christie. Our audiences didn’t know what TBTB was. We had a cast of nine artists, seven of whom were performers with disabilities. And at the end of the show when people would read the program it was like, “Where was the disability? I saw one actress in a wheelchair, but I thought that was a character choice!” This world is full of limitations. And in our lifetime, we may never see a wheelchair user working as a construction worker on a high rise, we may never see a person who is completely blind doing brain surgery. What we do as artists is create our own world and set our own limitations.

MT: “If you can believe in a singing crab in a Disney show, why can’t you believe in a person with a wheelchair playing an able-bodied role?”

NV: We say it all the time, but disability is a human characteristic. Sometimes you’re born with a disability, sometimes it comes to you in your life. As you age, the chances are you will have to deal with a disability at some point. Whether it is minor, whether it prevents you from being able to do something you were able to do earlier, that is a disability. Disability is personal. And it’s not.

We were talking before about hierarchies in our society and how we strive for equality and a level playing field, and this sounds negative, but we will never have a level playing field because our world and our society is one based on hierarchies. Who is smarter than whom, who is richer than whom, who lives here versus there, and we make judgments on that. And as long as we’re making judgments on those levels, there will always be the haves and the have nots. There will always be someone who we can point to and say, “’You’re different because you don’t have what we have.” It’s human, but that doesn’t mean we can’t keep working on that. Our goal for this company is to change the perception of disability and make people realize it is simply a human characteristic, and not something that invokes pity, not something that makes a person lesser-than. In fact, anybody who has a disability but lives in this city who is able to survive and exist and get around and do things – they are the truly incredible and true survivors. We always say the strong survive, but it’s not the strong, it’s the ones who are adaptable to change. And change is one of those things that – it’s the only constant in our life. We don’t like change, we’re creatures of habit, we like to know that when we roll out of bed the floor will be there, the water will be on, and we’ll be able to get to our favorite coffee shop. And when that changes, it’s earth shattering.

MT: Any general goals and challenges?

NV: Ike Shamblin, the founding artistic director of this company, started this company back in 1979 and he ran it virtually single-handedly for almost the entirety of its existence. This little off-Broadway, essentially community theater, existed for 38 years with such great potential, but he was only able to grow the company as big as one person can grow a company. You can be the hardest worker in the world, but there are only so many hours in the day and one person can only reach out to so many people.

My goal now is to grow this company and blow the walls out and grow our administrative staff and try to get more money. We need to do more work. Because, if we’re going to change perceptions, we need to be out there all the time, tapping people on the shoulder saying, “Come see this.”

MT: Is that why it went from Theater for the Blind to Theater Breaking Through Barriers? Was that part of that perception shift?

NV: It was a part of our expansion. It was also for practical reasons. The disabled performing arts community in New York City is probably one of the largest in the country – but that’s not saying much; it’s a very small community and everyone knows everyone else. If you decide to limit it further, and focus on just one disability, you’re really narrowing the field and you really have just a handful of actors. It got to a point where Ike was working with the same actors and casting shows for the same actors and felt constrained by it. I really pushed for this change. One of the things we’re fighting against is being discriminated against as a disabled performer. What we were doing is discrimination in itself, and why would we do that? So we need to change the name and open it up. Many of our blind actors felt that they were losing their company and losing their identity, and we had to say, no, you’re not losing it, you’re gaining something and growing the company. Some people didn’t like it and walked away. But it was the best move we could have ever made for the company and it changed everything. The work became richer. [The Healing] would not have happened if we were just theater by the blind. It’s a great gift. And what that taught me was that if I see myself limiting anything, I need to check that. Do we really want to limit ourselves? One of the reasons that our world is in the mess it’s in right now is because of the closures that we make and the judgments that we make.

The other goal is that there are so many different types of disability and I want to be able to work with anybody. We haven’t even gotten into working with artists with mental disabilities. That’s a very unique experience and it depends on the artist and the project, but it’s all a possibility and it’s all something I hope to do.

MT: What’s coming up next for TBTB?

NV: In March, we’re going to be bringing back our short play festival, which we haven’t had for a couple of years. We used to do plays about disability; we don’t want to do that anymore. I’ve reached out to a lot of different playwrights and I want to do plays about otherness in our society. I want that otherness to focus on racial otherness, sexual orientation otherness, religious otherness, social otherness. The plays will be called “The Other Plays.” That’s the title of the festival and it is going to be a group of plays – and the idea is that the playwrights will write these plays knowing that they’re going to be performed by performers with disabilities. I don’t want the otherness to be disability, because the point is disability is one diversity that cuts through all other diversities. We want to examine transgender and race and religion through a lense of disability.

MT: Any fun commissions coming up, from other writers? Do you guys do it every couple of seasons or every season?

NV: I don’t have any actual formal commissions, but I’ve spoken to several different writers and I’ve asked them to write for us. Lameece Issaq, who is with the Noor Theatre, she is Arab American, and I would love for her to write a play about that experience. I’m just curious about the experience of being an Arab-American female in our world today. That role could be played by someone with a disability. Dennis Allen, who is a wonderful playwright, who does a lot of work for Theatre Harlem, I’ve asked him to write. I’ve also asked Neil LaBute to write. Now Neil LaBute, that’s going to be an interesting one, because his plays are always very misogynistic. But I think he could really come up with something really interesting when it comes to social otherness. I’m also especially fascinated because I’ve asked this other writer, Basil Kreimendahl – Basil is transgender so a lot of Basil’s work focuses on transgender issues. And I’m thinking, how cool would it be to bump Basil’s play up against Neil LaBute’s play. With a short play festival, you want a bunch of different perspectives thrown at you. As for other writers, Neil was interested in writing a full length for us, as was Bekah Brunstetter. There are a lot of writers out there I’d love to have.

Here’s the hard part – there are a lot of people I want to work with, but I also have to think, as a small off-Broadway theater company, we do very few shows per year and we have to make those shows count. We have to sell tickets. My biggest goal is to draw people in to see our work. So if I have a playwright I’m interested in but no one else really knows them, I can’t do the show, at least not right now. So my goal is to keep building so I can get back to doing a three-show season and I can have a brand new play by Sam Hunter, a fun crowd-pleasing play like a Neil Simon company, and another play by a new up-and-coming playwright. That will allow us to introduce new writers, as does the short play festival.

MT: Other than, from my knowledge, New York Deaf Theatre, I believe you are the only two companies in New York City that cater to disabled artists. Beyond donating money and showing up to support the productions, what can people without disabilities, people wanting to help, do?

NV: Perceptions of what disabilities are need to change. I think we have a good shot at really making a change through theater, through film, through television. America was the pioneer that innovated many things, and one thing we still do better than anyone else is entertainment. There are other parts of the world that produce more entertainment, but people look to us. The world learns about America through our television and our films – that’s why our stars and celebrities are such commodities. The sad part of it though, is that perceptions won’t change as long as it is misrepresented, or represented in a way where it becomes, “we’re going to have a celebrity winning an Oscar for playing a disabled person.”

Normalizing what disability is is really the only way to help change that. And I think it’s that way with everything! And talking about it helps, when we talk about racial diversity, religious diversity. The more we can talk and come to an accord that the bottom line is we’re all just people. We’re all human beings who are inhabiting the same planet, and there’s so much more to us than our bodies. Take the time to look at how absolutely special and unique every person is, because every person’s life experience is unique. You’re a walking story book, you’ve got stories that are your own that nobody else has. It’s overwhelming, but it’s true.